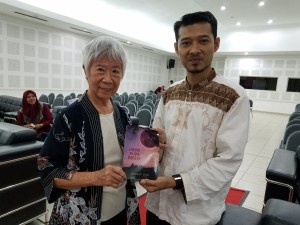

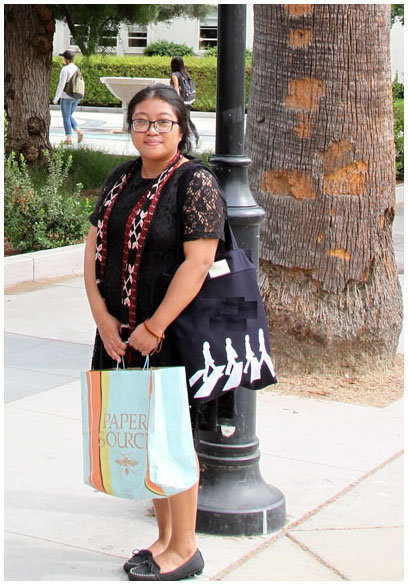

Novita Dewi started writing poetry and short stories during her elementary and middle school days. She published in Si Kuncung and Bobo, children magazines, as well as wrote for the children’s columns featured in Kompas and Sinar Harapan (now Suara Pembaruan). She now nurtures her interest in literature by writing articles about literature and translation for scientific journals. Novita is widely published. The short stories translated and published by Dalang Publishing are her first attempts of literary translation.

She currently teaches English literature courses at Sanata Dharma University, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Novita can be reached at novitadewi@usd.ac.id or novitadewi9@gmail.com.

The Regent’s Turmoil

Purwodadi, Central Java, Indonesia, October 1901

The moonless night crept toward midnight. Soeroto crouched among the sugarcane stalks and watched the house of the sugarcane plantation guard at the edge of the field. Suddenly, not far from him, he saw dozens of people approaching from the north side, next to the forest. The mob carried machetes and axes.

Soeroto had spied on this mob’s actions over the previous days. He had heard a rumor that they planned to burglarize the plantation and steal the workers’ wages. He moved stealthily closer to the house.

The band of bandits spread around the house, positioning themselves by the doors and windows. After a while, a stocky man, who appeared to be the leader, knocked on the front door.

Soeroto shifted in his hiding place to see better.

The knocks became louder and louder, trying to awaken the occupants of the house.

Apparently, the rumors Soeroto had heard about planned burglaries of the houses of the rich and the sugar factory were true. Conflicts like this could exacerbate the tension between Mas Adipati Brotodiningrat, Soeroto’s master, and Resident Donner. Resident Donner for sure was going to accuse his master of being behind this trouble.

“Who’s there?” a voice shouted from within. “Why are you knocking on the door at night?”

“You’ve 400 guilders in this house,” shouted the ring leader. “Surrender, before I break the door down!”

“You are alone! How dare you rob my house? I’m Sarmin, the plantation guard and the master of this area!”

Among the sugarcane stalks, Soeroto weighed the situation from a safe distance. Sarmin might be able to defeat this burglar if he fought one on one, but it would be impossible to win a fight against dozens of these thugs. Soeroto decided not to intervene.

Sarmin shoved the door open and almost made the burglar fall.

The man quickly straightened and laughed.

But with one swift movement, Sarmin put a machete to the robber’s neck and smiled triumphantly.

The burglar didn’t seem agitated. He looked toward the back door of the house and nonchalantly said, “Take a look at your wife over there.”

Sarmin turned and saw a group of burglars surrounding his wife. The burglars had entered the back door while Sarmin was dealing with their leader at the front door. Now, they had taken his wife hostage. Sarmin had no choice but to give up.

Soeroto could do nothing except leave quietly. He would report this incident to his master, Mas Adipati Brotodiningrat, immediately.

***

Madiun, East Java, Indonesia, December 1901

The atmosphere at the Dutch-ruled Madiun Residency felt unusual. People looked tense, and security at the resident’s office entrance was tighter than usual. In the office, the Resident of Madiun, J. J. Donner, was in a meeting with Judge Adipoetro, the chief prosecutor of Madiun, and Patih Mangoen Atmodjo, the vice regent of Madiun.

“Resident Donner, we have to arrest the indigenous gang leaders in Madiun and its surroundings,” said Judge Adipoetro. “Without these leaders, other criminals will not dare carry out another burglary.”

“It’s true, Resident,” added Patih Atmodjo. “Kartoredjo, the head of the irrigation department, also needs to be arrested. He not only has close ties to the gang leaders, but he was also the right-hand man of Brotodiningrat, the former Javanese regent of Madiun. Brotodiningrat must still be secretly in control of the criminals through Kartoredjo.”

Resident Donner paced the meeting room. Frowning, he said, “Soeradi, who stole curtains and tablecloths belonging to the residency, was caught in Ponorogo, but the stealing and burglaries continued. I believe Brotodiningrat is behind all of this unrest.”

“We could increase the night watch,” Adipoetro suggested.

Donner ignored him. “I think this theft of curtains and tablecloths was more than just a random crime,” he said quietly. “Brotodiningrat must be aiming for something bigger. He may want to create the same unrest on Java as the Javanese Prince Diponegoro did in 1825 with the Java War.”

Donner walked over to Patih Atmodjo’s seat and continued, “By prompting chaos like this, Brotodiningrat wants to weaken the position of our Dutch East Indies government. I also suspect that he used Islamic clerics to strengthen his position. Patih Atmodjo, what do you think of the teacher, Kiai Kasan Ngalwi?”

Patih Atmodjo opened the report in front of him. “Kiai Kasan Ngalwi often leads processions while praying along the village streets. He must be gathering support from the people to back the Brotodiningrat rebellion.”

Donner looked worried. He sat down, then stood up again. “Rebellion is in sight. I don’t want us to be caught by surprise. I will order firearms to be distributed to the Dutch Europeans for self-defense. I will also order the presence of armed guards around Paron station to protect the sugarcane train. The two of you continue to observe the movements of Brotodiningrat’s followers. This is a dire situation. We must be vigilant.”

“At your service, Resident,” replied the vice regent and the chief prosecutor in unison.

***

Pakualaman, Yogyakarta, January 1902

Soeroto, Brotodiningrat’s spy, rode on horseback into the Pakualaman area of Yogyakarta, a neighborhood where only aristocrats lived. He had just arrived from Madiun.

Recognizing Soeroto, the guard hurriedly allowed him to enter.

Brotodiningrat was resting in his private quarters when he heard galloping hoofbeats. He peered through the slats of his window to see who the visitor was. Seeing Soeroto, he walked quickly towards the pendopo, a large, covered terrace for receiving guests. Brotodiningrat had been waiting for news from Madiun and was expecting Soeroto’s arrival.

“Greetings, Raden,” Soeroto called out, using the Javanese term to address a nobleman. Soeroto saluted Brotodiningrat when he entered the pendopo.

“Soeroto! I have been waiting for you for a long time. Please, sit down. What news do you bring from Madiun?”

Soeroto waited for Brotodiningrat to be seated first. Then, after seating himself, Soeroto said, “The situation in Madiun is getting worse, Raden.”

Brotodiningrat considered Soeroto’s words and said, “Tell me specifically what is going on in Madiun.”

“Of course, Raden. Remember the theft of curtains and tablecloths from Resident Donner’s house in October three years ago? My news is still connected to that incident.”

“How could I forget it! It is what forced me to leave Madiun to live in this city,” Brotodiningrat grumbled, annoyed.

“Such incidents have increased,” Soeroto continued. “Not only burglaries, but burning sugarcane plantations around Madiun is also rampant. This past October, a burglary took place at the house of a plantation guard near the sugar factory in Purwodadi. The thieves stole the plantation workers’ wages of 400 guilders. The thugs are also targeting the homes of wealthy people in Ngawi and Magetan.” Soeroto’s voice had risen.

Brotodiningrat listened calmly, then said, “I told the former Resident of Madiun how to handle it. But this new resident, Donner, is stubborn and doesn’t want to listen to people who are experienced in handling such incidents.” Brotodiningrat paused before he continued. “Resident Donner is not like his predecessor, Resident Mullemeister. Mullemeister understands the Javanese way of dealing with problems like this. He would have left it entirely to the local regent and provided financial support for it.” Brotodiningrat sighed. “The current regent, Mangoen Atmodjo, is too weak. He is just a Dutch puppet. What does he know about the criminal world? How can he curb crime if he does not know anything about the underworld?”

Soeroto’s eyes darted anxiously. He seemed to have something more to say.

“You look restless, Soeroto. Is there anything else you’d like to talk about? If it’s about widespread burglaries, I have already expected those to happen with the appointment of the new regent.”

Soeroto hesitated. Drawing himself upright, he said, “Resident Donner is accusing you of being the instigator of the kraman, rebellion.”

“What?” Brotodiningrat roared. “How dare Donner accuse me of causing these uprisings!”

“Not only that,” Soeroto continued, “he has also detained a number of people who are close to you, such as the assistant resident, village policemen, even your teacher, Kiai Kasan Ngalwi, and Kartoredjo, head of the irrigation sector and your secret agent.”

Brotodiningrat’s face flushed with anger. “I thought Donner would be content after having me removed from my position as a regent. I guess he will not be satisfied until I am exiled from Java as a criminal.”

“Donner is utterly blind and unscrupulous, Raden,” Soeroto said. “He distributed firearms to the Dutch Europeans and reported to Batavia that there would be a new war on Java.”

“Donner has gone completely insane! New war on Java?” Brotodiningrat scoffed. “I just wanted to be a good regent who could maintain order and peace in Madiun.”

“Be careful, Raden,” Soeroto’s voice was filled with concern. “They are capable of arresting and prosecuting you. As I said earlier, your teacher, Kiai Kasan Ngalwi, has been arrested.”

“You are a loyal servant, Soeroto. You must be tired after the long journey from Madiun. Stay here for a day or two before returning.”

“Thank you, I will, Raden,” Soeroto replied and excused himself.

***

That night, Brotodiningrat couldn’t sleep. He thought this crisis had ended when he was exiled to Yogyakarta. But apparently, Donner still held a grudge against him. He seemed to want to prove that a Dutch resident was indeed more powerful than a native Javanese regent. The judge’s decision to remove him from the position of regent of Madiun on account of the robbery case obviously had not satisfied Donner.

Brotodiningrat thought back to when he was a teenager. He had gone to school in Surakarta and lived in the Kasunanan area. He could see how great Susuhunan Pakubuwono, the ruler of Solo, was. Brotodiningrat had stood tall as a Javanese native and had gained respect from the Dutch officials. The experience made an imprint on Brotodiningrat’s memory, inspiring him to become a Javanese regent who could be equal to a Dutch resident.

He studied the Dutch language diligently so that he could speak to the Dutch as an equal. He also absorbed all his lessons concerning government affairs while studying to become a public administrator. He then assiduously underwent an apprenticeship as a scribe in Madiun. He understood that all of this had to be done to achieve his goal of being considered on par with the Dutch.

His dream came true when he was appointed Regent of Sumoroto, a province in East Java. Everyone, both native and Dutch, looked up to him.

But he felt that he was truly capable of achieving his dream when he met Mullemeister, then the Resident of Madiun, the person he had ever since considered his mentor. It was Mullemeister who proposed that Brotodiningrat be appointed Regent of Madiun. They worked well together. Resident Mullemeister gave him the freedom to take care of irrigation, security, and many other responsibilities. Working alongside Mullemeister, Brotodiningrat applied everything he had learned while studying for this governmental position.

Sadly, Brotodiningrat had to part with his teacher and best friend when Mullemeister was promoted to Resident of Yogyakarta, to work side by side with Sultan Hamengkubuwono, King of Yogyakarta. Such was truly a proper position for a resident as smart as Mullemeister. But unfortunately, Mullemeister’s promotion caused a disaster, because his Dutch successor, Resident Donner, was power hungry and didn’t trust the Javanese.

The trial accusing Brotodiningrat of orchestrating the theft of curtains and tablecloths from Resident Donner’s house was a long affair. Brotodiningrat had to be tried in Batavia. The good thing for Brotodiningrat was that Mullemeister worked desperately to defend him. The bad thing for Brotodiningrat was that the officials in Batavia wanted to save face and back Resident Donner, because if Donner’s accusations were found to be ungrounded, the Dutch East Indies colonial government would lose face.

During his one-year trial, Brotodiningrat was exiled to Padang. He was fortunate that his letters of self-defense, sent to Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands and Governor-General Rooseboom of the Dutch East Indies, were well received. Although he was removed from his position as Regent of Madiun, he was allowed to return to Java. Having been honorably discharged, he received a fairly high pension and could live in a house in Pakualaman, Yogyakarta.

But now he was being accused of rebellion. The Dutch East Indies officials must still be haunted by the Java War waged against the Dutch colonial rule by Javanese Prince Diponegoro. But accusing him of being the second Diponegoro was unsubstantiated. And to think that the Dutch authorities had even dared to arrest his teacher, Kiai Kasan Ngalwi! Brotodiningrat realized the precarious, dangerous situation he was in and decided to consult with Mullemeister, his best friend.

***

Since his exile in Pakualaman, Yogyakarta, Brotodiningrat’s connection to the outside world had been limited to correspondence and newspapers. He had indeed lost power. But the arrival of a letter from Mullemeister cheered him up.

The envelope was marked: Important and Confidential.

Brotodiningrat took the letter to his private room. Using a letter opener, he quickly slit the envelope and, his heart pounding, began reading.

Dear Brotodiningrat,

I hope you have heard that the colonial government sent Snouck Hurgronje to investigate the case related to Donner’s accusations against you. The results of the investigation have been completed, and I want to be the first to reveal them to you.

Snouck is indeed a reliable investigator. He is fluent in Arabic and Javanese, so he could carry out in-depth investigations. He was also able to ask many people in Madiun to explore this case. From Snouck’s investigation, it can be concluded that it was Donner himself who caused crime to increase in Madiun. He impulsively arrested your trusted people who had important connections in the underworld. After they were all arrested, there was no one to control the criminals, and they ran rampant.

But fear not, Snouck found no evidence against you. He even said that Donner was “too tired” and suggested that Donner retire and rest.

However, regarding the case of your teacher, Kiai Kasan Ngalwi, he must be sacrificed. The colonial government still has to keep up a good front. Your teacher was exiled because, otherwise, the public would think that the Dutch East Indies government has less power than Kiai Kasan Ngalwi. But don’t worry, his rights, including land rights, will be maintained, even though he must remain in exile.

I hope this crisis will pass quickly. Snouck seems to already have a new candidate to replace Donner. The colonial government does not want to repeat the same mistake by appointing another stubborn person like Donner to replace him. We all have had enough of this debacle.

Warm regards to your family.

Mullemeister.

This letter brought Brotodiningrat some relief. Mullemeister was indeed a reliable friend.

***

Pakualaman, Yogyakarta, mid-1903

Soeroto returned to meet Raden Mas Adipati Brotodiningrat, his master. This time, he rode his horse more casually as he slowly entered Brotodiningrat’s neighborhood. He was also much calmer than during his previous meeting with Brotodiningrat.

The guard immediately asked him to wait in the pendopo. Not long after, Raden Mas Adipati Brotodiningrat came out to meet him.

“Raden.” Soeroto saluted respectfully.

“Please have a seat, Soeroto. What news do you have this time?”

“You must have heard the latest rumors regarding Donner.”

“What do you know about Donner?”

“Donner must have lost his mind. He is going totally crazy!” Soeroto sneered. “Donner even dared to accuse the Susuhanan of wanting to rebel because he had received a warm welcome when he visited Semarang.”

Brotodiningrat couldn’t hide his smile of victory. “Donner really has gone mad. Fortunately, the government in Batavia was quite responsive and immediately dismissed the accusations of this insane person. Donner’s own thoughts were his undoing. He was convinced that there would be a second Diponegoro. He fantasized to the point of believing that I was the second Diponegoro!”

“It seems so, Raden,” replied Soeroto.

“What do you think of his successor in Madiun?” Brotodiningrat probed.

Soeroto, excited, said, “Resident Boissevain is quite capable. He fired the chief prosecutor, who was responsible for arresting your subordinates. All of your followers appear to be quite happy with the new resident’s actions. Those who were fired for their involvement in this incident have also been given new, albeit small, positions in Pacitan and Ponorogo. Security and order seem to have been restored.”

Brotodiningrat looked pensively eastward, as if trying to gaze at Madiun. “It seems so. But there is still one thing that bothers me, Soeroto.”

“What is it, Raden?” asked Soeroto, trying to read his master’s wishes. “Do you still intend to return to Madiun?”

“There’s that, too, but it seems too early to say. We still have to see how things develop.”

“Then what is troubling you, Raden?”

“You have served me for a long time, Soeroto. You’ve been with me since I was accused of masterminding the curtain and tablecloth burglary at Resident Donner’s house.”

“Inggih, yes, I have, Raden.”

Brotodiningrat gave Soeroto a sharp look. “What do you think of our position as Javanese natives versus the Dutch colonial rule?”

“I dare not answer, Raden. I let smart people like you think about such questions.” Soeroto acted awkwardly, as if afraid to say the wrong thing as an ordinary citizen.

“You have to start thinking about it, Soeroto. I sense a wind of change — maybe not like the emergence of a Diponegoro. But the world will change.”

“What do you mean Raden?”

“Freedom, Soeroto. Independence. Freedom to determine our own destiny, freedom from the colonial rule of the Dutch East Indies.” Brotodiningrat smiled as he imagined that future.

“It’s too hard for me to imagine that, Raden. For me, it is enough if I have clothing, food, and a roof to sleep under.”

“It’s not wrong to continue thinking that way, Soeroto. I, too, only recently thought about this. After going through the never-ending tempest with Donner, I started to contemplate what my real position had been in the Dutch East Indies government. Was I really equal to the resident? Or would I forever remain a Dutch lackey?” Brotodiningrat stood. “Resident Donner thought I was his subordinate, not an equal official. However, there was a clear division of labor. He supposedly took care of matters with Batavia’s and Madiun’s external affairs, while I took care of Madiun’s internal affairs.” Brotodiningrat’s tone rose every time he talked about Donner.

“Has he held a grudge against you since that incident?” Soeroto asked softly.

“Yes, I believe so. But I also often badmouthed him and compared him unfavorably to Mullemeister, who is much more shrewd than Donner. Mullemeister can mingle with the local officials and understands Javanese manners.” Brotodiningrat paused for a moment then grumbled, “Donner must have been offended.”

“You are lucky to have met Mullemeister.”

“Yes, indeed. Mullemeister has helped me so much. I was able to escape prosecution, although I still lost my job. This has strengthened my belief that we, the Javanese, are not on the same level as the Dutch.”

“Do you remember the writings of your cousin, Raden Mas Tirto Adhi Soerjo, in Pembrita Betawi?” Soeroto asked suddenly. “He defended you and said that it was an injustice! Lots of people talk about his writings.”

“How could I forget? That cousin of mine is great! Last month, he dared to write a newspaper article in the column Dreyfusiana. The article’s title is written in capital letters: THE DONNER SCANDAL. He interviewed many Dutch officials about this case. I have to admit that the news influenced public opinion including that of the Dutch Europeans regarding this case. People now know that Donner is a lunatic!”

Brotodiningrat took a deep breath and then continued, enthusiastically, “Tirto was also so bold as to said that I should be tried like a Dutchman, based on evidence, not hearsay.”

“That’s right, Raden,” Soeroto agreed, excited. “That’s what many people say.”

“Soeroto, we must be equal to the Dutch, not only in terms of the law, but we must also receive the same education. I was lucky to study in a Dutch school because I am a descendant of the regent. But you, a commoner, will never have the chance to go to school. You can only be a servant or a spy, like you are now.”

“Inggih, Raden.” Soeroto bowed his head.

“I see you’re quite smart. If you could go to school, you might learn Dutch and then become a clerk or even a sugarcane plantation supervisor. But you won’t have such an opportunity unless things change.”

“I dare not to have such lofty dreams, Raden.” Soeroto’s head was still bowed.

“You must! You must dare to dream!” Brotodiningrat nodded vehemently. “Soeroto, times will change. Tirto already had that vision, and I confirmed his thoughts. We have to fight for our equality with the Dutch.”

“Does that mean we have to be free from the Dutch colonial government, Raden?” Soeroto asked.

“We must fight for our equality with the Dutch!” Brotodiningrat repeated.

“What does that mean exactly, Raden?”

“That means that there must be a People’s Council, consisting of indigenous people, who can make recommendations to the Governor-General.” Brotodiningrat grew even more excited. “We must be given the opportunity to determine our own destiny.”

“You have such complicated thoughts. I find it difficult to follow you.”

“That’s fine, Soeroto. I may even suffer from this overly advanced thinking. Maybe the government in Batavia has secretly read my desire to fight for more equal rights for us, the indigenous Javanese people.”

“Do you mean to say that you were dismissed from the position of regent because you have been too brave and challenged the Dutch?” Soeroto asked in disbelief.

“You’re smart, Soeroto. I was too daring and challenged the Dutch. Maybe it’s not the time yet for this fruit of independence to ripen and fall from the tree. Now, new little flowers are blooming timidly. Some will later become fruit, and some of that fruit will ripen. I saw that in my cousin, Tirto.”

“Of course, Raden.”

“The end of our struggle is still a long way off, Soeroto. But mark my words, this nation’s conflict with the Netherlands, like the Donner case, will not be the last. This time we won, partly, but there will be bigger conflicts later. You are my servant; take my spirit into the future, so our nation can still win when dealing with the Netherlands.” Brotodiningrat’s eyes were fiery with enthusiasm, even though his position of power had been extinguished.

*****

.