Remembering Padewakkang

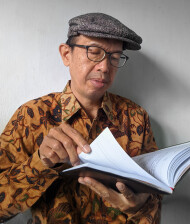

Award winning author Junaedi Setiyono was born in Kebumen, Central Java, on December 16, 1965. He received all of his education from grade school to university in Purworedjo a small city near Yogyakarta, Central Java. In 2013, Setiyono was awarded a scholarship by The Ohio State University in Columbus, Ohio, to conduct research as a part of his doctorate degree in language education, which he received in 2016 from the State University of Semarang.

Setiyono worked as a high school English teacher. Since 1997, he has taught at his alma mater in Purworejo, usually on the subjects of writing and translation.

Setiyono’s short stories have been widely published. His first novel, Glonggong (Penerbit Serambi, 2008), won the Jakarta Art Council Novel Writing Award in 2006. In 2008, the same novel was on the five-title shortlist for the Kusala Sastra Khatulistiwa Literary Award, which recognizes Indonesia’s best prose and poetry. His second novel, Arumdalu (Penerbit Serambi, 2010), was on the ten-title shortlist for the Khatulistiwa Literary Award in 2010. In 2012, the manuscript for what would become his third novel, Dasamuka (Penerbit Ombak, 2017), won the Jakarta Art Council Novel Manuscript Award. The novel was translated into English in 2017 and published under the same title by Dalang Publishing. The novel won the 2020 literary award of the Indonesian Ministry of Culture and Education.

Currently, in addition to writing his next novel, Setiyono is also researching how teaching the English language can be a catalyst to promote Indonesian teaching in Indonesia.

Setiyono can be contacted via his email: junaedi.setiyono@yahoo.co.id

*****

Remembering Padewakkang

ARNHEM Land, Australia, December 1945

Holding a wooden tobacco pipe that had not been lit for a long time, Burarrwanga Dayn Gatjing stared at the horizon. He waited for the merchant ships from Makassar, which used to cast their anchor here. Decades ago, the southeast winds that blew in March and April had blown the padewakkang sails northward. Their departure had been like losing a part of himself.

However, Burarrwanga, the dark-skinned, gray-haired chief of the Yolngu tribe the natives who lived in the region — had never lost hope that once again, just like a long time ago, the baarramirri, the northwestern winds that blew in December and January, would bring back the padewakkang vessels to moor in these waters. People would once again crowd the coastal area, filling their baskets with the teripang, sea cucumbers, they had gathered. Some of them smoked their catch. The image of such a beautiful time was ingrained in Burarrwanga Dayn Gatjing’s memory. He kept waiting for Daeng Gassing and the other Makassar sailors, who came from the other side of ocean and brought rice, gold, and tobacco. Some hundred years ago, the Makassaran people had first come to Arnhem Land. The good relationship they established with Burarrwanga’s ancestors and the natives of Arnhem Land had been maintained all this time.

“Perhaps they were swallowed by the thunder snake in the middle of the ocean,” said Marika, Burarrwanga Dayn Gatjing’s wife.

“Don’t talk nonsense. The thunder snake only attacks the wicked men at sea. Good men, like the Makassar sailors, wouldn’t be sunk.”

“Never mind, Burarrwanga,” Marika said. “There is still that tamarind tree they planted. You can take a rest under it.”

“I haven’t heard you call me by that name for a long time. The last time you used it was when they were here, right?”

“Yes, everyone, even the white men, now know you better as Dayn Gatjing than by your birth name.”

With a heavy sigh, Burarrwanga Dayn Gatjing recalled what the white men had done to his life. The padewakkangs were gone. They had been banned forty years ago by the Australian Commonwealth for irrational reasons. Now, only the white men sailed back and forth, ruling the ocean and exploiting its wealth, especially the teripangs. The Yolngu people were no longer involved in any of the trading and did not receive anything the Australian Commonwealth took everything.

Burarrwanga would never forget the days when the coastal area of Arnhem Land was crowded by padewakkangs, merchant vessels owned by Makassaran people.

***

It was quite hot during the month of January in 1905. It was as if the sun’s heat was multiplying. Despite the conditions, bare-chested, barefooted ship crews and Yolngu people continued to lift bamboo baskets filled with just-harvested teripangs from the seabed. These sea cucumbers were taken to a smoking place where Daeng Gassing, captain of one of the docked Makassaran trade vessels, sat taking notes of how many pikuls of teripangs were collected that day. Each pikul weighed about 133 pounds.

Sitting next to Daeng Gassing, Burarrwanga smoked his pipe and watched members of his tribe working with the Makassarans. The pipe was a gift from his father, who in turn had received it as a gift from a Makassaran sailor quite a long time ago. Almost all of the adult males in Burarrwanga’s tribe owned such a pipe. They called it pipa Makassar because the Makassaran sailors were the ones who brought these pipes to them from the other side of the ocean.

“I’ve used the tobacco you gave me when you came a year ago.” Burarrwanga exhaled smoke through his nostrils. “But now you’ve brought me more again.”

“This is a custom our people have upheld over hundreds of years,” Daeng Gassing said while making notes Burarrwanga could not decipher. The Yolngu were illiterate. When they wanted to remember something, they drew or carved pictures on wood or stone. “Every year, we Makassaran merchants bring you certain items. In return, your people help us gather the teripangs.”

“We wouldn’t be doing so well if your men didn’t come here to gather teripangs.” Burarrwanga grinned. “You can take all of them. We don’t eat them.”

“Teripangs actually taste pretty bad,” Daeng Gassing agreed. “No one in Makassar eats these strange animals, either. We sell them in China, where sea cucumbers are expensive. Your teripangs are good quality.”

“I hope that one day I can visit your home. I am sure your native village is prosperous and developed.” Burarrwanga sighed before asking, “Are there a lot of ships and big houses?”

“If were prosperous back home, we’d unlikely be here looking for teripangs.” Daeng Gassing paused a moment before continuing. “There are many problems back home especially after the Dutch took control over Makassar. On the other hand, we are happy to come here. I’m sure this is also making our ancestors happy.”

The Makassaran sea captain most likely did not fully realize the enormity of the great changes the Makassarans had brought to the lives of Arnhem Land’s natives over the centuries. Along with bringing them rice, metal, tobacco, and liquor, the Makassar merchants also brought other goods that the people of Arnhem Land had never seen before. Arnhem Land became a part of the Makassar sailors’ homeland. They called this land Maregeq because of an old rumor that said Arnhem Land was a part of the Gowa Kingdom.

During Burarrwanga and Daeng Gassing’s conversation, Marika, who was more than six months pregnant, suddenly came running towards them. “The Commonwealth men …,” she panted, stumbling towards them. “I saw them … they’re carrying guns ….” Marika stood in front of her husband and the captain, shaking and gasping for breath.

Daeng Gassing and Burarrwanga quickly alerted their men. The Makassaran sailors grabbed their machetes and axes while the Yolngu men prepared their spears and arrows. They didn’t like violence, but if the Commonwealth men came armed, they had to be prepared for every possibility.

Soon, an Australian Commonwealth constable stood in front of Daeng Gassing. “You have strayed too far from your homeland, and you’re harvesting too many teripangs in an area which is not yours. Consider this a warning.”

“My ships have been registered by the harbormaster of Port Bowen,” Daeng Gassing retorted. “What are you warning me for?”

“Look at this.” The constable took out a piece of paper. “I have orders to watch all of you Makassarans because you’re a bad influence on these natives. You’re causing them to become drunkards.”

“Hey, this is not your business, is it?” Burarrwanga raised his voice. He didn’t like the Australian Commonwealth interfering with their lives. “Why do you bother us?”

“Listen.” The constable shot Burarrwanga a sharp look, then continued while pointing at Daeng Gassing, “These men — only God knows where they came from — will get you in trouble.”

“You have no say here!” Burarrwanga suddenly swung at the constable. His punch was a bit off target, but the constable lost his balance and fell backward. He drew his pistol and fired a warning shot into the sky.

Startled, those around Burarrwanga covered their ears.

Both the Makassaran and Yolngu men reached for their weapons, ready to attack the group of white-skinned constables. But Daeng Gassing signaled to hold off the attack.

“Because this is only a warning, we will leave,” said the constable. “We don’t want any violence here, but one punch deserves another.” The blond constable landed a well-aimed punch on Burarrwanga’s cheek and left.

People crowded around the dazed Burarrwanga. Some of them made ready to chase the constable, but Burarrwanga signaled them to stop. The constable’s punch made Burarrwanga see stars and many kangaroos jumping around him. Everything turned blurry then became dark. He fainted.

***

Two years after the incident in 1905, the Australian Commonwealth banned Makassar ships from entering Australian territory. This was worse than the storms that frequently hit the padewakkangs while crossing the ocean. Makassaran fishermen had come to harvest teripangs off the Arnhem Land coast since the mid-1600s. The olive-skinned ancestors of Daeng Gassing had sailed to Arnhem Land much earlier than any of the white-skinned Commonwealth men who arrived on these shores with thousands of prisoners and rifles.

On the night before the padewakkangs lifted anchor from Arnhem Land for the final time, Burarrwanga sat staring at the flames of the fire that absorbed the silence. Time passed, as a dozen men sat around the fire without uttering a word. The only sounds that broke the silence were the breaking waves sweeping the sand, the creaking boards of ships swaying in the water, and the crackling of broken branches being swallowed by the flames. The men gathered around the fire were confused, angry, and sad. It was unlikely that after the padewakkangs set sail the next day, they would ever see each other again.

Burarrwanga raked the fire with a branch. For a moment he rested his eyes on the pile of ashes in the fire pit. It occurred to him that the ashes resembled their hopes. Burarrwanga sighed, then blew onto the smoldering branches until he became dizzy. Suddenly, many thoughts somersaulted inside his head. It was as if the kangaroos he used to hunt in the savanna had jumped into his head. He could leave with the sailors, whom he’d known for as long as his memory could serve him. He contemplated the fate of his tribe and his descendants if he decided to move to Makassar with his family.

Across the fire, Burarrwanga saw Daeng Gassing’s gloomy face lit by the dancing flames. Burarrwanga wondered why the man with the thick moustache and long hair looked sad. Afterall, he and his crew were about to go home. Burarrwanga had spoken his thoughts.

“Are you sure you want to leave Arnhem Land?” Daeng Gassing’s voice broke the silence.

“I have to.” Burarrwanga threw some branches into the flames. “The Australian Commonwealth men have taken everything. There is nothing left that I am able to protect. We cannot live without you and your men.”

“But what about your tribe? You will just leave everyone?”

“The elders will choose a new chief after I’m gone. This is the last opportunity for me to cross the ocean and see something behind the horizon. I want to have a better life for my wife and son.”

The two men stared at one another. The heat of the fire seemed to move into the eyes of the two men who had become like brothers.

Daeng Gassing didn’t want Burarrwanga to abandon his tribe, but there was nothing he could do. He had no right to keep Burarrwanga from pursuing his dream.

Marika rose and broke into their thoughts. “Yesterday, I met a mother. When I told her that we were leaving, the woman dropped to the ground, crying. She punched the sand repeatedly while begging me to stay.”

Daeng Gassing bowed his head. He held a bamboo mug containing ballo, an alcoholic drink from Makassar made from coconut flower sap. He rose and handed the mug to Burarrwanga. “Tonight is the last time to have fun together. There is still plenty of ballo where this came from. Drink up!”

Burarrwanga happily accepted the mug.

“I don’t want to go,” Marika said between chews on the roll of betel leaves in her mouth. “I was born here, and I want to die here too.” Her words surprised everyone sitting around the fire.

“I can’t leave you and our son,” Burarrwanga said. “I am ready to leave everything, but not you.” Burarrwanga shook his head. “No that I cannot do.”

It was a dark and gloomy night. People started arguing. After Marika stated her preferences openly, other people started joining in the discussion. Most of them did not want Burarrwanga to leave for Makassar. The departure of the Makassaran men already hurt them. If Burarrwanga, their chief, who protected their land with his bravery against the Australian Commonwealth forces, was gone too, they would be totally lost.

Arguing bitterly, Burarrwanga, his people, and Marika could not reach an agreement. Burarrwanga stubbornly held on to his opinion. He intended to take Marika and their son with him to Makassar, even if Marika herself didn’t want to accompany her husband and even though his council of elders had already forbidden him to do so. Suddenly, Burarrwanga felt very sleepy. He abruptly rose and, leaving the fire, headed for his hut. He needed to get some sleep.

The discussion ended without any solution.

***

That night, in Burarrwanga’s dream, he rose and looked around. His heart pounding, he searched nervously for Daeng Gassing and the other Makassaran men. Burarrwanga didn’t see any of them. He, his wife, and his only child were supposed to leave for Makassar that day.

The sky began to brighten. In the distance, the sun started to rise gradually, while the morning star seemed reluctant to leave. Did the padewakkangs sail without me? Burarrwanga wondered. He suspected that Daeng Gassing and his crew had betrayed him, but Burarrwanga had considered those men to be his friends. He remembered that Daeng Gassing and some of the Yolngu men hadn’t agreed with his decision to follow Daeng Gassing to Makassar. Irritated and feeling deceived, Burarrwanga looked for his tribe’s men.

He was astonished not to find anyone. Even the hut they had built was empty. Where are they? Had they been kidnapped by the Australian Commonwealth men?

“No, they haven’t been kidnapped,” came a shout from afar.

Burarrwanga looked around anxiously, but there was no one. He had clearly heard someone shouting, someone responding to his inner dialogue. Burarrwanga looked around again. A kangaroo sitting on top of a dead coral rock, was the only living creature around.

“Are you lost?”

Burarrwanga fastened his eyes on the dead coral rock again, but the kangaroo had vanished. How strange, Burarrwanga thought, a talking kangaroo. He began to wonder if what was happening was real or if he was dreaming. It was impossible for a kangaroo to talk!

“Burarrwanga Dayn Gatjing, are you simply going to abandon your tribe?” The kangaroo again appeared on the dead coral rock.

“Who told you that my name is Dayn Gatjing?” Burarrwanga shouted, rubbing his eyes. “My name is just Burarrwanga!”

“Oh, you will find out, soon. Just wait a moment.” The kangaroo then turned into an olive-skinned woman.

Burarrwanga could hardly believe his own eyes. The woman’s skin color resembled that of the Makassaran people, lighter than the skin of the Yolngu people. The woman floated through the air. With a wave of her hand, the hills became as flat as the plains. Rivers flowed to the sky and then fell as soft rain. The sun, which had already risen halfway into the sky, suddenly sunk again. Night came, and stars emerged and circled in the sky around Burarrwanga. Other beautiful things appeared like paintings. The night was not just black. It was a hazy combination of red, green, blue, yellow, and other colors Burarrwanga had never seen before. The colors seem to spill around him. Burarrwanga was astonished seeing such a scene.

“You …” Burarrwanga stammered, “are you Baiyini, the First Being of the Yolngu people?”

“I am whoever you think I am, Dayn Gatjing. These are all my paintings. I send them to the world you live in.”

“You … are you Mimi, the painter’s spirit? No, you … you are Barnumbirr, the spirit of creation.” Burarrwanga knelt, but the mysterious creature asked him to rise.

“Take heart and return to your people,” said the spirit. “You are only lost. You are afraid that this land will continue to disappoint you. But you must remember that your ancestors stood firm for thousands of years. They were here long before the Makassaran merchants moored their padewakkangs here and long before the white-skinned people fired their first gunshot here. You will be all right for decades, even centuries to come. Just stay here and remember those who have to depart.”

Burarrwanga woke up crying. He could still hear the apparition’s advice. Now he understood. He had visited a wongar, the dream place where the Yolngu’s ancestral spirits lived and created this world. Not just anyone could visit there. According to the elders, only the chosen ones were given guidance in a dream and could enter the gate to wongar to see the creators in their real form. Burarrwanga had just received such guidance and, therefore, had been blessed.

***

The ashes of the previous night’s fire were still piled on the beach. The tide was already high. Crew hands were busy carrying the last baskets containing dried teripang onto the padewakkangs. The southeast wind started to pick up. The ship crews began preparing the sails. The anchors would soon be lifted. But Daeng Gassing still stood on the beach.

“You decided not to go quite suddenly,” he said to Burarrwanga. “Did you have a dream?”

“Yes, I was in a wongar and met a kangaroo. It is difficult to explain. In short, my tribe’s ancestors asked me to stay here.”

Daeng Gassing could not understand Burarrwanga’s behavior. How could someone who only the night before was so eager to leave this land and sail to Makassar change his mind just because of a dream — a dream about a kangaroo that had advised him to stay?

But that was Burarrwanga’s belief. Whether or not he met his ancestor or whoever in a mystical world, Daeng Gassing didn’t want to pursue it further. He was relieved that Burarrwanga had changed his mind about leaving his homeland and his people. The only thing that Daeng Gassing wanted to ensure was that Burarrwanga would keep fighting to get back his homeland’s rights from the Australian Commonwealth people.

“By the way, may I take your name and add it to the end of my real name?” asked Burarrwanga. “My new name would then become Burarrwanga Daeng Gassing or, using the Yolngu pronunciation, Burarrwanga Dayn Gatjing!”

“Is it a sign of brotherhood?” Daeng Gassing asked.

“I will pass down the Makassaran name and tell the story about you to my son, my grandson, the grandson of my grandson. Call me Burarrwanga Dayn Gatjing!”

“Of course. We will possibly meet again one day, when the baarra season comes and the mamirri blows.” Daeng Gassing was not sure if he had used the proper Yolngu terms.

“Hah!” Burarrwanga laughed. “It’s baarramirri, the season when the wind blows from the northwest.” Burarrwanga raised his hand and waved goodbye for the last time. The Yolngu people around him followed his gesture. Everyone’s eyes remained glued to the padewakkang sails until they vanished in the horizon.

*****