Introduction to 2025 series of short stories.

Dalang published Footprints / Tapak Tilas, the 49 short-story, bilingual compilation in 2022. The publication celebrated our tenth anniversary and acknowledged the contributing 44 authors and 18 translators. This launch resulted in the seven short stories to be featured here in 2025.

Each of these short-story authors represents one of the seven areas Indonesia is known for.

During the Footprints / Tapak Tilas launch event in each region, we asked the audience for questions and offered a competition. The most in-depth question submitted, that would help an up-and-coming author or translator, would win and receive a copy of Footprints / Tapak Tilas. The winners were requested to write a short story and promised that the professionally edited work and its translation would be featured on our website.

These authors are mostly young, aspiring writers with a keen interest in literature and sense of nationalism. We hope that being published on our website will give them a foothold into the literary world and inspire them to continue the journey with their writing muse.

Our stories are not only geared to develop writing skills, but are also aimed at nurturing Indonesian literature with the hope of breaking through international walls. As for our foreign readers, we hope our stories bring enlightenment regarding Indonesian customs, culture, history, and society. For the Indonesian readers, we hope to awaken and/or nurture a sense of pride in their home country and the bounty it has to offer.

A recording of the events can be found at:

https://sites.google.com/view/bincangsastra-eng/beranda

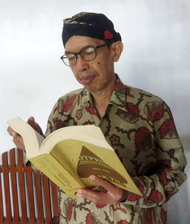

Junaedi Setiyono

Junaedi Setiyono received a scholarship from Ohio State University to conduct research as part of his doctorate degree in language education, which he received in 2016 from the State University in Semarang, Central Java. He felt being part of Dalang Publishing after he was entrusted with the edit of Lolong Anjing di Bulan (Sanata Dharma University Press 2018), a novel by Arafat Nur, and the translation of two short stories: Mengenang Padewakkang, by Andi Batara Al Isra, and Ketuk Lumpang, by Muna Masyari — both published in 2022 in Dalang’s Footprints/Tapak Tilas, a bilingual short story compilation.

Setiyono’s most recent assignment — to edit the 2025 series of six short stories to be published in installments on Dalang’s website — gave him the opportunity to improve his own writing skills, including accurate word placement, appropriate sentence structure, and careful examination of the storyline’s plausibility as composed by the author.

Dalang has published two of Setiyono’s novels: Dasamuka (Penerbit Ombak 2017) and Tembang dan Perang (Penerbit Kanisius 2020).

Setiyono teaches writing and translation at his alma mater, the Muhammadiyah University of Purworejo. He received three awards for Dasamuka from: the Jakarta Arts Council; the Indonesian Ministry of Education and Culture; and the Southeast Asian Literature Council.

Junaedi Setiyono: junaedi.setiyono@yahoo.co.id

Terre Gorham

Terre Gorham has spent her entire life coaxing words to sing. Briarcliff Elementary School “published” her first short story when she was in 2nd grade. She went on to earn a degree in writing. She freelanced her work until she landed a full-time job as editor of The Downtowner Magazine, in Memphis, TN, where she wrote, edited, and guided young writers for more than 20 years. Gorham has ghost-written a novel for a non-profit organization that helps abused women. She joined Dalang Publishing in 2017 as the English language editor. Her words have been published in hundreds of publications. She is currently working for an event production company where she edits documents ranging from client presentation decks to policy manuals. Now, nearing “retirement age,” she continues her editing work on a freelance basis once again.

Terre Gorham: terregorham@gmail.com

Rolin

Falantino Eryk Latupapua is published in scientific journals and books of literary and cultural studies. His poems are published on social media and in the anthologies Pemberontakan dari Timur (CV. Maleo, 2014) and Biarkan Katong Bakalai (Kantor Bahasa Maluku, 2013).

Perempuan Naga, his first short story, was translated into English by Umar Thamrin and published on Dalang Publishing’s website in March 2023. Rolin is his second short story, completed while teaching Indonesian to non-Indonesian speakers in Vienna, Austria. He taught the same program online at the Indonesian Embassy in Oslo, Norway.

In 2005, Latupapua began teaching at his alma mater, the University of Pattimura. He earned his master’s degree from the Faculty of Cultural Studies, Gadjah Mada University, in 2011, and his doctorate degree with cum laude honors in literary and cultural studies from the Faculty of Cultural Studies, University of Indonesia, in 2025.

Latupapua writes songs and sings with his music group, KAK5. As an instructor, judge, and resource for music and literary programs, he runs cultural activities with artists in the Maluku Islands.

Falantino Eryk Latupapua: falantinoeryk@gmail.com

*****

Rolin

“Nona!”

Perempuan itu berbalik. Wajahnya datar, tidak tampak terkejut. Rinduku membuncah. Jantungku hendak pecah tertusuk sorot matanya. Rambut keritingnya masih mengembang seperti dulu. Hanya saja, helai-helai uban sudah terselip di sana.

Kedua kakiku terus gemetar. Aku menarik napas dalam untuk menenangkan perasaanku.

“Ose Nona, kan?” sergahku sebelum dia sempat berbicara. Aneh sekali rasanya menyebutkan ose yang berarti “kamu” dalam bahasa Melayu Ambon. Sejak tinggal di Bekasi, baru kali ini aku menggunakan bahasa ibuku.

“Maaf … Anda siapa?” tanyanya lirih. Matanya membelalak. Ada kebingungan dalam nada suaranya.

“Nona, ini beta … Rolin…!”

Deru kendaraan menenggelamkan suaraku. Aku melangkah mendekatinya.

“Beta Rolin. Masih ingat?”

Nona bergeming. Tubuhnya bergetar. Wajahnya memucat. Tatapannya menguliti jilbabku. Mulutnya menganga.

Aku menatapnya lekat-lekat. Dengan lidah, kudorong dua gigi seri palsu di belakang bibir atas hingga terlepas dari gusi dan bergeser ke depan. Pada detik berikutnya, kukembalikannya gigiku ke tempat semula — kebiasaanku bila didera kecemasan.

Tubuh Nona tampak goyah. Air matanya meleleh. Aku pun berjuang menahan ledakan tangisku. Ketika dia mendekatiku dengan kedua belah tangan direntangkan, aku hanya diam mematung.

Tiba-tiba aku tersentak, teringat pada Abu, suamiku. Aku mundur selangkah dan menoleh ke arah laki-laki itu. Aku khawatir dia melihat kami. Ternyata, dia masih bercakap-cakap dengan rekan sepengajian yang berpapasan tadi, sambil menggenggam tangan kecil Ri, cucu kami yang berusia empat tahun. Ibunya, Mina — anak perempuan kami satu-satunya — telah berpulang pada usia delapan belas tahun, beberapa hari setelah melahirkan anak itu. Sedangkan ayah Ri, laki-laki bejat itu, menghilang setelah meninggalkan benihnya dalam rahim Mina. Orang sekeras dan setertib Abu pun gagal “melindungi” anaknya. Inikah teguran dari Tuhan?

Aku kembali menatap Nona. Dia tidak lagi berusaha memelukku. Dia bisa membaca ketakutanku.

“Kenapa ose seng pulang, Rolin? Ose punya orangtua seng selamat. Katong kira ose sudah meninggal juga. Ternyata ose masih hidup.” Kata-kata Nona menghunjam telingaku. Aku menelan ludah, hilang tenaga untuk bicara.

“Aku takut … malu.” Suaraku hampir tidak terdengar. Ingin aku bercerita tentang getir yang membelenggu. Kisah mengenai aku yang hilang lalu kembali sebagai mualaf bukanlah kisah yang mudah diterima. Mereka tidak akan mengerti rindu pulang yang harus kupendam demi mengabdi pada Abu — dengan menggadaikan kebebasanku.

Bibirku tidak sanggup lagi bergerak. Air mataku makin deras mengalir. Hatiku terasa sangat pilu.

Di tengah derai air mata, sudut mataku masih bisa menangkap kelebat Abu yang menyudahi percakapan dengan rekannya.

“Maaf, Nona. Beta seng bisa berlama-lama,” tergesa-gesa aku mengeringkan air mata dengan ujung lengan baju.

Kulihat Nona pun menghapus air matanya dengan sebelah tangan. Secepat kilat, dia merogoh tas yang diselempangkan di bahu kirinya, mengeluarkan secarik kertas dan sebatang pensil, menulis sesuatu dengan terburu-buru, lalu menjejalkannya ke dalam genggaman tanganku.

Mataku menangkap sederetan angka di kertas itu. Nomor teleponnya. Aku memasukkannya ke dalam saku bajuku.

Nona menatapku dalam-dalam. Matanya masih basah, tetapi dia tidak lagi bicara.

Sedetik kemudian, aku membalikkan badanku sambil memejamkan mata lalu menghela nafas. Aku melangkah meninggalkannya.

Abu menatapku sembari berjalan mendekat. Ri sudah meringkuk dalam gendongannya.

“Siapa itu?” Abu bertanya dengan tatapan penuh selidik. Tatapan semacam itu telah ratusan kali kuterima — saat aku berbicara dengan orang asing, saat dia memergokiku sedang menonton tayangan televisi tentang kota kelahiranku, atau membicarakan peristiwa masa lalu. Bagi Abu, sesudah aku memutuskan hidup sebagai istrinya berarti aku harus mengabdi sepenuh jiwa dan menghapus kenangan masa lalu.

“Perempuan itu, Bang? Dia menanyakan alamat seseorang. Aku tidak kenal.” Aku berusaha menyembunyikan kegugupan dengan menunduk dan mengebaskan bagian bawah baju dengan kedua tanganku seolah ada kotoran menempel. Begitulah kebiasaanku yang lain — selain memainkan gigi palsuku — kalau dilanda kecemasan.

“Ya, sudah. Kita pergi saja!” Abu berbalik, melangkah menuju tempat pemberhentian bus. Aku mengiringinya dengan pikiran yang berkecamuk. Aku ingin sekali pergi bersama Nona. Aku ingin pulang.

***

Di dalam bus yang kami tumpangi menuju Bekasi, Abu tertidur sambil mendekap Ri. Dadaku masih berdebar-debar. Wajah Nona masih belum pergi dari hadapanku. Aku takjub dengan perjumpaanku dengannya, pertemuan yang terjadi di tempat yang ribuan kilometer jauhnya dari kota kecil tempat kami dulu tinggal.

Nona adalah sahabat masa kecilku. Rumahnya bersebelahan dengan rumah orangtuaku di Ambon, kota kecil tempat kami lahir dan tumbuh bersama.

Kami sering tidur sekamar, berdempetan seperti ikan julung kering — begitulah Ibu selalu berkata saat menggambarkan kedekatan kami.

Aku menatap ke luar jendela bus, berusaha mengalihkan pikiran dari perjumpaanku dengan Nona. Tetapi, memandang gedung-gedung pencakar langit yang berjejeran semakin membuatku menderita menahan kesedihan.

Aku tidak akan pernah melupakan hari terkutuk itu — Minggu, 7 Mei 2000 — saat kapal feri celaka itu terbenam ditelan gelombang lautan. Hari yang ingin kulupakan seumur hidupku, tetapi terus menghantuiku lewat mimpi buruk; mimpi-mimpi yang tidak pernah sekali pun kuceritakan kepada Abu.

***

Pada Sabtu sore, sehari sebelum peristiwa itu, aku, ayah, dan ibuku sudah berada di Pelabuhan Gudang Arang untuk berlayar ke Pulau Seram. Suasana sangat ramai; ribuan orang dan puluhan kendaraan memadati pelabuhan. Itu adalah perjalanan laut pertama sekaligus yang terjauh bagiku. Sebelum itu, Ayah mendidik kami, aku dan saudara-saudara sekandungku, dengan keras. Kami tidak pernah diizinkan pergi jauh dari rumah.

Di beberapa sudut pelabuhan, puluhan tentara bersenjata lengkap sedang berjaga-jaga. Beberapa dari mereka berkeliling, seolah mereka ada di setiap penjuru kota. Seperti hari-hari sebelumnya, kota Ambon terus dicekam ketakutan. Sejak malam hingga menjelang subuh terdengar suara senapan mesin dan bom bersahut-sahutan.

Sudah lebih dari setahun kota Ambon berubah menjadi neraka. Orang-orang Islam dan Kristen saling menyerang, membakar, melukai, bahkan membunuh. Pada Idul Fitri yang kelabu itu, 19 Januari 1999, dua orang sopir angkot — yang satu beragama Kristen sedangkan yang lainnya beragama Islam — terlibat pertengkaran di simpang Desa Batu Merah, tidak jauh dari Desa Hative Kecil tempat kami tinggal.

Pertengkaran itu memicu kerusuhan yang merambat ke wilayah-wilayah lain di kota itu. Kota kecil yang tadinya tenang dan damai itu berubah menjadi ajang peperangan yang sungguh-sungguh menakutkan. Dalam setahun, ribuan orang harus mengungsi karena rumah mereka hangus dibakar atau dijarah tanpa ampun. Banyak keluarga kehilangan anggotanya. Mereka terbunuh dengan amat kejamnya — tertembak atau tertebas senjata tajam. Malapetaka itu membuat orang-orang yang bersaudara pun harus terpisah hanya karena memeluk agama yang berbeda.

Perjalanan itu kulakukan untuk memulai pengabdianku di Desa Waihatu, Seram Barat. Ayah dan ibuku bersikeras ikut mengantarkanku. Aku mengartikannya sebagai kepedulian kedua orangtuaku — wujud kebanggaan mereka. Beberapa bulan setelah lulus perguruan tinggi, aku berhasil menjadi guru sekolah dasar. Kebahagiaan dan kecemasan campur aduk saat namaku, Anna Carolina, terpampang di pengumuman kelulusan — bangga karena meraih pekerjaan impian, tetapi cemas meninggalkan orangtua dan saudara.

Tidak lama setelah peluit berbunyi tiga kali, kami menaiki kapal feri putih-biru bertingkat dua, menyerupai kotak sepatu raksasa. Masnait…. Aku ingat guru SMA-ku pernah mengatakan bahwa kata Masnait berasal dari bahasa kuna yang berarti pemimpin pelayaran.

Kapal itu menaikkan jangkar lalu mulai berlayar ketika hari beranjak malam. Hujan deras dan angin kencang menampar badan kapal. Pada tingkat bawah, bus, truk, dan sepeda motor berjejalan hingga nyaris tidak menyisakan ruang. Pada tingkat atas kapal itu, ratusan orang berdesakan di ruangan penumpang, di antara tumpukan koper, tas, kardus, dan juga karung berukuran besar yang dihamparkan di setiap sudut ruangan. Banyak sekali bayi dan anak-anak yang ikut berlayar. Bayi-bayi itu menangis bersahutan, sementara beberapa anak kecil berlarian di sepanjang lorong kapal.

Perjalanan itu memakan waktu sekitar dua belas jam, begitu kudengar lamanya waktu berlayar dari percakapan beberapa orang. Kapal harus mengitari bagian selatan Pulau Ambon menuju Seram Barat. Biasanya, jalur dari Pelabuhan Hunimua ke Pelabuhan Waipirit hanya memakan waktu dua jam. Namun, kerusuhan itu menyebabkan Pelabuhan Hunimua di Desa Liang yang berpenduduk Muslim, tidak aman untuk dijangkau penumpang Kristen, sehingga jalur kapal itu dialihkan menuju Teluk Ambon.

Kami beruntung karena bisa menghuni kamar milik Cao, salah satu kerabat kami, juru mesin di kapal itu. Di dalam kamar itu ada dua ranjang kecil, kursi, meja, serta sebuah lemari kecil. Barang bawaan yang cukup banyak dijejalkan di bawah tempat tidur. Setelah menyantap bekal aku dan Ibu berbaring berdesakan, sementara Ayah menempati ranjang lainnya.

Guncangan kapal akibat gelombang laut terasa semakin menggila ketika kapal itu sudah berlayar sekitar satu jam. Kedua orangtuaku sudah lelap. Sementara aku masih terjaga. Aku menatap ke luar jendela kecil kamar itu. Kelap-kelip lampu rumah penduduk semakin samar. Aku merasa kapal itu sudah meninggalkan teluk dan mulai melayari lautan bebas. Tidak lama kemudian aku terlelap dalam buaian gelombang.

Tiba-tiba aku terbangun ketika ayah mengguncangkan tubuhku sambil memanggilku. Deru mesin telah berhenti, tetapi kapal masih oleng diayun gelombang. Ayah menuntunku untuk keluar. Air laut menggenangi lantai kapal. Teriakan orang-orang bersahut-sahutan. Aku menyadari bahwa kapal itu telah miring ke arah buritan. Lampu telah padam, hanya tersisa remang sinar lampu darurat. Ibu bersandar di dinding luar kamar dengan wajah dicekam ketakutan.

Kejadian itu berlangsung dengan amat cepat. Teriakan peringatan dari awak kapal bersahut-sahutan dengan jerit tangis ketakutan yang semakin menggila. Kami bertiga berpelukan sambil menangis. Ayahku berdoa dengan suara yang tenang dan dalam, tetapi isak tangis tidak mampu ditahannya. Aku membuka mata dan berusaha menatap wajahnya. Untuk pertama kali dalam hidupku, aku melihat air matanya.

Bagian buritan kapal semakin terbenam. Ayah menuntun kami yang saling berpegangan tangan ke arah haluan. Banyak orang berjejalan di sana. Sebagian telah melompat ke dalam gelapnya lautan yang bergelora. Genggaman tangan orangtuaku lepas saat kami terpaksa harus melompat dari haluan kapal sebelum kapal benar-benar ditelan gelombang lautan. Aku berjuang sekuat tenaga, menendang-nendangkan kaki dan mengayunkan tangan, sambil berteriak minta tolong. Aku berkali-kali meneguk air laut. Saat tenaga hampir habis, aku berhasil meraih selembar papan yang mengapung dan memeluknya dengan sisa kekuatan. Suara-suara lenyap, malam tetap gulita, dan laut terus bergelora. Pikiran kosong, tubuh gemetar kedinginan. Air mata terus mengalir – tangis tanpa suara. Aku ingin berteriak, tetapi telah kehilangan daya.

Aku terombang-ambing di lautan, nyaris kehilangan kesadaran. Lamat-lamat kudengar bunyi kapal dan teriakan beberapa laki-laki bersahut-sahutan. Aku tidak berani membuka mata. Kesadaranku menghilang setelah tubuhku ditarik keluar dari lautan.

***

Aku terjaga tanpa membuka mata saat mendengar suara beberapa perempuan berbicara pelan. Tubuhku terasa hangat. Di luar sana terdengar suara azan, persis seperti yang biasanya kudengar dari pengeras suara masjid di kampung tetangga. Mulutku terasa sangat asin. Pelan-pelan ingatanku pulih. Aku ingat Ayah yang berdoa dan Ibu yang ketakutan. Telingaku seakan bisa mendengar bunyi gelombang, deru mesin kapal, dan teriakan ketakutan orang-orang.

Aku membuka mataku. Aku berada di dalam ruangan luas dengan langit-langit tinggi yang diterangi cahaya lampu yang remang kekuningan. Aku berusaha melihat ke sekitarku, mencari-cari kalau-kalau ayah dan ibuku ada di sana. Tidak ada siapa-siapa selain dua perempuan dengan bedak dingin di wajah mereka. Mereka menatapku dengan pandangan menyelidik. Tubuhku yang lemah tanpa tenaga mulai gemetar dan berkeringat dingin. Aku teringat ibu-ibu penjual ikan berbedak dingin dari kampung Muslim yang sehari-hari berjualan ikan di desa kami. Aku di kampung Muslim sekarang! Isak tangisku tidak tertahankan, kesedihanku bercampur dengan ketakutan yang teramat sangat. Cerita-cerita tentang beberapa orang yang terjebak dan dibunuh di kampung-kampung Islam memenuhi pikiranku.

“Dia sudah siuman! Dia siuman!” suara para perempuan bergumam dengan pelan. Kedua perempuan itu mendekat. Salah seorang menyapukan tangannya di dahiku lalu mengusap-usap rambutku sambil menyodorkan segelas teh ke dekat mulutku. Seorang lagi meremas-remas ujung jari kakiku.

“Minumlah ….” perempuan itu berbisik padaku.

Aku berusaha mengenyahkan ketakutan yang sedang menguasaiku. Pelan-pelan aku memalingkan muka. Kugerakkan bibirku untuk menangkap ujung sedotan yang dibenamkan ke dalam gelas lalu menyesap isinya. Aku menatap perempuan itu dengan penuh rasa terima kasih. Dia terlihat lebih tua beberapa tahun dariku.

“Beta di mana ini?” suaraku nyaris tidak sanggup kukeluarkan dari kerongkonganku. Perempuan-perempuan itu terdiam. Sejenak mereka saling bertatapan.

“Assalamu’alaikum!” suara berat seorang laki-laki mengagetkan kami. Aku menoleh ke arah pintu yang setengah tertutup.

“Wa’alaikumsalam…!” Para perempuan itu menjawab hampir bersamaan sembari menoleh ke arah datangnya suara itu.

Daun pintu terbuka lebih lebar. Seorang laki-laki melangkah masuk. Aku memberanikan diriku menatapnya. Dia mengenakan jubah putih. Di puncak kepalanya disangkutkan semacam topi putih seperti laki-laki India yang kusaksikan di televisi. Janggutnya lebat, menjuntai ke dadanya. Apakah laki-laki ini adalah anggota laskar yang sangat terkenal karena kebengisan mereka membantai orang-orang Kristen selama kerusuhan ini? Aku menelan ludah. Rasa dingin yang aneh menjalari kaki tanganku sementara butir-butir keringat halus semakin melelehi tubuhku. Ini adalah hari kematianku. Ya Tuhan, selamatkanlah aku dari kekejaman mereka!

Laki-laki itu melangkah menuju tempat aku dibaringkan. Beberapa laki-laki lain berjalan mengiringinya. Mereka terlihat amat menaruh hormat padanya. Perempuan-perempuan yang bersamaku pun menunduk dalam diam. Tidak berani menatapnya.

“Kalian layanilah dia dengan baik.” Ujar lelaki berjubah putih itu lalu berpaling menatapku. “Jangan takut …. Kamu aman di sini!”

Aku tidak kuasa mengangkat wajahku. Sekujur tubuhku menggigil pelan oleh ketakutan yang teramat sangat. Namun, aku bisa merasakan kehangatan dalam nada suaranya, meskipun dia berbicara dengan suara berat dan tegas. Seketika itu juga, aku tersihir oleh pesona wajah rupawan dan pembawaannya yang tenang, meskipun rasa takutku tidak hilang begitu saja. Hari itu adalah awal pertemuanku dengan Abu, pemimpin tertinggi laskar bersenjata dari Pulau Jawa yang ikut berperang dalam kerusuhan itu, yang kemudian menjadikanku istrinya.

***

Bus tua ini nyaris tidak bergerak. Bekasi sudah dekat tetapi kemacetan semakin menggila. Inilah yang membuatku begitu membenci kota ini.

Aku merogoh saku baju, mengeluarkan secarik kertas pemberian Nona. Guratan angka-angka pada kertas itu hampir tidak terbaca. Aku meremasnya lalu membiarkan gumpalan kertas itu jatuh dan bergulir di lantai bus. Maafkan aku, Nona .… Aku telah ikhlas dan menerima semuanya, aku berbisik dalam hati sambil menahan tangisanku yang hendak pecah.

Aku menarik napas berat dan menoleh ke arah Abu dan lelaki kecilnya yang masih tertidur, seakan membeku dalam deraan udara yang amat pengap. Aku menatap wajah Abu yang mulai digurati keriput halus di sana-sini. Mungkin karena dia tidak pernah berkata kasar kepadaku apalagi menyakitiku, aku mencintainya sepenuh hati, meski rasa takutku padanya tak pernah benar-benar pergi.

Dua bulan sejak pertemuan pertama di pagi hari sesudah kecelakaan feri itu, aku dijadikan istri siri Abu. Beberapa minggu sebelum akad, dengan dituntun ustad, aku bersyahadat di hadapan Abu dan jamaah masjid di sebuah kampung kecil di Pulau Seram. Setelah itu, aku berpindah-pindah, mengikuti Abu dari kampung ke kampung, pulau ke pulau, tanpa pernah bertanya tentang pekerjaannya. Beberapa kali, aku mendengar Abu berbisik-bisik dengan beberapa kawannya tentang jumlah laskar yang mati, tentang wilayah yang telah ditaklukkan, atau tentang bantuan dana dari Jawa yang belum juga diterima.

Menerima pinangan Abu adalah jawabanku atas panggilan nasib yang tidak lagi dapat kutolak. Jalan pulang telah terhalang oleh cengkeraman kerusuhan berdarah. Harapan untuk memeluk keluargaku lagi, atau sekadar menyampaikan kabar bahwa aku masih ada, telah luruh oleh pekik perang dan gemuruh senapan.

Menjadi istri siri Abu adalah satu-satunya jalan paling aman dan paling masuk akal untuk kupilih sebagai seorang perempuan yang tidak sanggup melawan deraan rasa takut. Aku selalu bersyukur akan kenyataan bahwa Abulah yang menyelamatkanku, meskipun dia bersama laskarnya telah memerangi dan membunuh banyak orang. Demikian pula ketika aku mengetahui bahwa aku adalah istrinya yang ketiga, perempuan kedua yang dijadikannya istri siri selama melanglang buana dalam kerusuhan berdarah di kotaku. Ya. Aku mencoba untuk berdamai dengan semua itu. Menjadi mualaf dan menjadi istri ketiga Abu adalah jalan yang tidak pernah kubayangkan tetapi bisa kuterima dan kujalani dengan tabah.

***

Laju kapal yang kami tumpangi kian melambat. Orang-orang mulai hilir-mudik dalam keriuhan. Setelah empat hari bergulat dengan kenangan buruk kecelakaan dua puluh tahun lalu, berakhirlah penderitaanku.

Aku mengguncang-guncangkan tubuh Ri yang masih terbaring di sampingku. Dia terbangun lalu menatapku dengan mata bulat yang mirip sekali dengan kakeknya.

Abu meninggal dua minggu yang lalu, setelah bertahun-tahun berjuang melawan sakit paru-paru. Sebagai istri siri, aku dipinggirkan begitu saja oleh istri tua dan anak-anaknya. Dengan sisa-sisa uang yang kumiliki, aku membayar biaya kapal untuk diriku dan Ri.

Setelah semua kehilangan dan kepahitan hidup yang harus kukecap tanpa bisa kutolak, aku menyadari bahwa takdir tidak bisa kulawan. Menerima dan menjalaninya sesungguhnya adalah cara terbaik untuk bertahan dan mencintai kehidupan.

“Para penumpang yang budiman, KM Dobonsolo telah bersandar di Pelabuhan Yos Soedarso, di Kota Ambon. Bagi Anda yang hendak turun, kami mohon untuk memeriksa seluruh barang bawaan Anda. Tangga turun berada di tingkat tiga sisi kanan arah buritan kapal. Terima kasih!”

Aku menegakkan tubuh Ri, mengancingkan baju hangatnya, lalu menggendongnya. Satu-satunya tas besar berisi pakaian yang kami miliki kusampirkan di bahu kananku.

Kami pun bergerak pelan mengikuti iring-ringan penumpang menuju tangga kapal. Aku tidak kuasa menahan air mata. Dengan matanya yang bulat bening, Ri melihatku menangis. Dia memelukku makin erat. Pelataran pelabuhan itu basah, berkilatan diterpa butir-butir halus gerimis yang beterbangan ke segala penjuru. Di puncak tangga, kota mungil bergelimang cahaya di kaki perbukitan menjulang itu terasa menyambutku. Di bawah sana, lautan manusia dengan ratusan payung yang terbuka bersiap menyambut sanak keluarga yang baru tiba. Dengan sentakan pelan, aku merengut jilbabku hingga lepas lalu melarungkannya ke arah permukaan laut. Kain hitam tipis itu melayang pelan hingga menyentuh permukaan laut lalu perlahan menghilang di keremangannya.

Aku memejamkan mata lalu menghirup dalam-dalam udara hangat yang kurindukan dengan tidak terperikan. Begini rupanya rasanya pulang!

Aku membuka mata. Wajah Abu membayang di langit yang temaram. Dia menyeringai, menahan sakit dalam sakratul maut yang mencengkeramnya. Tidak seorang pun memedulikan kematian lelaki pendiam yang hampir tidak punya kawan itu — termasuk para istri yang lain serta anak-anak mereka.

Selamat jalan, Abu. Semoga dilapangkan jalanmu. Maafkan aku atas ketidaksanggupan menjaga amanah dan baktiku terhadapmu. Aku mengusap air mataku, membetulkan gendongan Ri, lalu menuruni anak tangga dengan perlahan, satu demi satu.

*****

Rolin

Purwanti Kusumaningtyas teaches at the English Literature Bachelor’s Program, Faculty of Language and Arts, Satya Wacana Christian University in Salatiga, Central Java. She earned her master’s and doctorate degrees from the American Studies Graduate Program, Faculty of Cultural Science, Gadjah Mada University, Yogyakarta. She has a wide range of interests, including mountain climbing and hiking, as well as poetry and short-story writing.

She has published her poems and short stories in anthologies, among others, “Furtive Notions” (DeePublish 2022) and “They Are Here” (DeePublish 2023). Some of her poems have been musicalized and performed in various non-profit, humanistic events, including LETSS Talk, a prominent feminist initiative in Indonesia, and Festival Musik Rumah (FMR). She has worked with Dalang Publishing since 2013, after discovering that she and the publisher share a passion to preserve and introduce Indonesia’s diversity to the world.

Purwanti can be reached at: purwanti.kusumaningtyas@uksw.edu

*****

Rolin

“Nona!”

The woman turned around. She didn’t look surprised. My heart pounded under her inquisitive gaze. Her curly hair looked the same as I remembered it — except now it held strands of gray.

My legs trembled. I took a deep breath to calm myself.

“Ose Nona, aren’t you?” I rushed to ask before she could say anything. I lived in Bekasi, a suburb of Jakarta, so it felt strange to use the Ambonese Malay word for “you.” This was the first time I’d used my mother tongue in a long time.

“Sorry … who are you?” Her voice was soft . Then her confused eyes widened.

“Nona, this is beta — me, Rolin!” My voice almost disappeared amid the cacophony of vehicles. I stepped closer. “I’m Rolin. Remember me?”

She froze, and her face lost color. Staring at my hijab, her lips parted.

Apprehensively, I pressed my tongue hard against my two false front teeth — so hard, they shifted. I quickly sucked them back into place. This was a nervous tic of mine whenever I became anxious.

Nona swayed slightly, tears spilling unchecked. I struggled to restrain my own sobs. As she approached me with outstretched hands, I froze.

Suddenly, I remembered Abu, my husband, and startled. I stepped back, worried that he had seen us. But no, Abu, was still deep in conversation with one of his Quran study friends, holding the hand of our four-year-old grandson, Ri.

Ri’s mother, Mina — our only daughter — had died several days after delivering Ri. The child’s father had disappeared after finding out that Mina — then only 18 years old — was pregnant with his child. Abu, despite being as tough and as strict a man as he was, had failed to “protect” his child. Or … was it God’s warning?

I looked again at Nona. She had stopped when I stopped, her hug undelivered.

“Rolin, you’re alive!” Nona’s voice cut through the traffic noise. “Rolin, we thought you had died with your parents! Why didn’t you return home?”

I swallowed. “I was scared … embarrassed,” I whispered. How could I tell her about the bitterness that now smothered me? How could she understand my conversion to Islam, that I had pawned my freedom and heritage for the sake of loyalty to Abu?

My lips couldn’t form the words, but tears flowed. My heart ached. I saw Abu wrapping up his conversation with his friend.

“I’m sorry, Nona, I can’t be long.” I hastily dried my eyes with the hem of my sleeve.

Nona also wiped her eyes. She reached into her bag and took out a small piece of paper and a pencil. After a quick scribbling, she pressed the note into my palm.

I glanced down. Her phone number. I carefully tucked the note into my pocket.

Nona’s eyes, still wet, searched mine, but she didn’t say anything more.

Taking a deep breath, I turned and walked away.

Abu, carrying Ri in his arms, gave me the once-over as we walked toward one another.

“Who’s that?” Abu asked with a curious look. I had seen that expression hundreds of times — whenever I talked to a stranger, whenever he caught me watching a television show about my hometown, whenever I talked about the past. Being Abu’s wife meant complete devotion and a total break from what was.

“Oh, that woman?” I hid my agitation by flicking the lower part of my long dress, as if to remove some dirt — another nervous tic. “I don’t know. She was asking for directions.”

“All right, then let’s go.” Abu turned and headed toward the bus stop. I followed behind, thoughts in disarray. I really wanted to go with Nona. I wanted to go home.

***

During the bus ride home to Bekasi, Abu slept with Ri in his arms. My heart was still racing. Nona’s probing look was still clear in my mind. What were the odds of our meeting, thousands of kilometers away from our hometown?

Nona had been my childhood friend in Ambon, the little town where we were born. We often slept in the same room, packed tight like a container of dried julung fish — that’s how my mother had described our closeness.

I looked out of the bus window to divert my thoughts from the encounter with Nona. But the clusters of skyscrapers made it even harder to shake off my nostalgia.

The old bus crawled through the dense traffic as it neared Bekasi. This is what made me hate this city.

I took out the piece of paper Nona gave me. The scrawled numbers were almost illegible. Slowly, I closed my fist, crumpled the paper into a small ball, and dropped it on the bus floor. Forgive me, Nona … I have accepted my fate and come to terms with it.

I took a deep breath and stole a glance at Abu and our grandson, still sleeping as if frozen in the stuffy air. Abu’s face was older now, with a few fine wrinkles. Perhaps because he never spoke harshly to me or ever hurt me, I loved him wholeheartedly. My fear of him, however, never really disappeared.

My thoughts traveled to that doomed day — Sunday, May 7, 2020 — when the ocean waves rose to swallow the ill-fated ferry boat. The tragedy replayed its dreamlike terror in my sleep, but I never told Abu about these haunting nightmares.

***

On that Saturday afternoon, one day before the accident, my parents and I were at the Gudang Arang Port to sail to Seram Island. The harbor was packed and noisy; thousands of people and dozens of vehicles crowded the port. It was my first sea travel and the farthest I’d ever been from home. My father had raised my siblings and me very strictly. We were never allowed to go far.

Here and there, groups of armed soldiers stood guard while others patrolled. They were everywhere. For more than a year, Ambon had been hell on Earth. Muslims and Christians attacked, maimed, burned, and killed one another. As the constant stutter of machine guns and thundering bombs filled the air from dawn through the night, Ambon filled with fear.

On a gloomy Eid al-Fitr in January 1999, a fight had broken out between a Christian and a Muslim public transport driver, at an intersection in a village not far from where we lived in Ambon. The altercation triggered a wave of riots that spread throughout the town, turning the small, peaceful village into a terrifying battlefield.

In the year that followed, homes were looted and burned, turning thousands of people into fleeing refugees. Families were splintered — if not from being shot to death or stabbed then from practicing different religions.

***

From Gudang Arang Port, I was sailing to Seram Island to begin my service as an elementary school teacher. My proud parents had insisted on accompanying me, which I interpreted as a token of their love. When I had graduated from college and saw my name, Anna Carolina, appear on the announcement of graduates, happiness and worry collided — happiness because I acquired my dream of being a teacher; worry because I would have to leave my family and home.

The ferry’s whistle blew three times, and we walked into what looked like a giant two-story, white-and-blue shoe with the name Masnait painted on its side. I remembered my high school teacher telling our class that “masnait” was derived from an ancient language and meant “expedition leader.”

The ferry lifted anchor at dusk. Heavy rain and strong winds whipped the boat’s hull. Buses, trucks, and motorbikes crowded the lower deck of the ferry, leaving almost no space for people to pass. On the upper deck, hundreds of people huddled in the passenger lounge among piles of suitcases, travel bags, cardboard boxes, and sacks. Babies wailed while children ran through the passageway’s obstacle course.

From the conversations we overheard, the journey would take about twelve hours. Usually, the route only took two hours, but turmoil inside the nearest port, a Muslim settlement, made it unsafe for Christians to dock, and therefore the ship had to detour to the southern part of Ambon Island before moving toward West Seram.

We were lucky we had the use of a cabin, thanks to our relative Cao, the ship’s mechanic. His cabin had two small beds, a table and chair, and a small wardrobe. We stuffed our luggage under the beds and made a dinner of the food we had brought from home. Tired, my mother and I lay down on one of the beds while my father took the other.

The rough water made the ship pitch and roll violently. My parents were fast asleep; I was still awake. Peeking through the porthole, I saw my town’s lights fading far away. The ship was now in open water. Despite the turbulent waves, I fell asleep.

I startled when my father, shaking me, called my name. The rumbling vibrations of the engine had stopped, but the ship was still heaving and swaying. My father took my hand and led me out of the cabin and into chaos. Passengers shouted at one another. The hallway glowed eerily under the faint light of the emergency lamps. Mother, looking horrified, leaned against the wall outside the cabin. I became aware that the ship’s stern was sinking.

Everything happened so fast. The crew shouted warnings and instructions while people screamed and cried in terror. The three of us hugged each other. My father tried to pray calmly, but he couldn’t restrain his anguish. For the first time in my life, I saw his tears.

The stern continued its descent. We held hands as Father walked us up toward the bow, where others huddled. Then, people started jumping into the dark, hungry waves. My hand slipped from my parents’ as we jumped off the bow, right before the waves devoured the ship.

I struggled to stay afloat in the churning water, kicking, waving, and shouting for help. I kept swallowing sea water. Using the last bit of my energy, I grabbed a floating piece of wood and clung to it. I was no longer aware of anything except a murky night and roaring waves. My head felt empty, and I was very cold. Helpless, I cried, not having the energy to scream.

Drifting in and out of consciousness, I floated with my piece of wood. At some point, I faintly heard a boat’s engine and men shouting at each other. I didn’t dare open my eyes, even after strong arms pulled me from the water. Then, I fainted.

***

The next thing I knew, I was awake and warm. Keeping my eyes closed, I heard women talking softly. I could also hear the prayer call from afar. It sounded exactly like the call I usually heard from the loudspeaker of the mosque in my neighboring village. My mouth tasted very salty. Little by little, my memory returned. I remembered my father praying and my mother’s horror. I heard the waves, the ship’s engine, and unending screams.

I opened my eyes to a large room with a high ceiling, lit by a dim, yellowish light. Are my parents here? I saw no one except for two women with traditional bedak dingin, eyeing me curiously. I remembered seeing that same cooling face powder, made of crushed rice grains, on the faces of the women fish sellers in the Muslim village. Cold sweat spread over my weak body. I’m in a Muslim village! I’d heard stories about people who had been killed in Muslim villages. A scared sob escaped my mouth.

“She’s conscious! She’s conscious!” the women whispered excitedly as they hurried over to me. One woman massaged my feet while the other stroked my forehead, placing a glass of tea against my lips. “Drink this,” the woman whispered.

I positioned my head to catch the straw poking out of the glass. I sipped gratefully.

“Where am I?” I croaked, my voice a stranger in my throat. The women looked at each other.

“Assalamu’alaikum!” A man’s heavy voice from outside the door startled us.

“And peace be with you!” The women replied simultaneously as all three of us turned in the direction of the voice.

The door opened. A handsome man entered, wearing a white robe and the same type of white cap I had seen Indian men wear on television. He wore a thick chest-long beard. Is he a member of the militia murdering Christians during the unrest? I tried to swallow. Sweat chilled my legs and arms. Am I going to die? Is this the end of my life? God, please save me from their violence!

The man approached my bed. Behind him, several men followed in deferential silence. The two women bowed their heads and remained quiet, as if afraid to look at him.

“Treat her well,” said the man in the white robe. Then he looked at me. “Don’t be afraid. You’re safe here.” Through my fear, I could hear warmth in his firm voice and detect calmness in his demeanor.

That is how I met Abu, the supreme leader of Java’s rioting militia group, and the man who later married me.

***

Two months after our meeting, Abu and I “married,” following the religious doctrines that made me his common-law wife. Several weeks before the marriage ceremony, an ustad had guided me in proclaiming my conversion to Islam in front of the members of a small mosque on Seram Island. After that, I followed Abu unquestioningly from one place to another, from island to island and village to village. Several times I overheard Abu tell his friends about his militia men who had been killed, about the area they had conquered, or about the funds from Java that they had not received.

Accepting Abu’s marriage proposal had been the answer to my fate that I couldn’t ignore. My way back home had been thwarted by the bloody unrest. My hope to embrace my family again, or at least to send news that I was still alive, had disappeared in screams on the battlefield and rumbling gunshots.

Becoming Abu’s wife was my only safe and reasonable choice. I always felt thankful for the fact that Abu saved me, even though he, together with his militia, had fought and killed a lot of people. My feelings for him didn’t change even after finding out that I was his third wife — and the second woman he’d married following the religious agreement but without legal registration to the government. Yes. I had to make peace with all those facts. Converting to Islam and becoming a common-law third wife was a way of life I had never imagined I could accept and live with fortitude.

***

Our ship moved slowly, carrying Ri and me toward Ambon. I shook Ri gently. He woke and stared at me with his grandfather’s big, round eyes.

After fighting lung disease for years, Abu had died two weeks ago. His children and first wife — the legal one — evicted me, who was only a third, common-law wife. With the remaining funds I had, I paid the ship passage for Ri and myself.

Passengers began moving around noisily. After four days of struggling with the bad memories about the accident twenty years ago, I reached the end of my suffering.

After all the loss and bitterness of life I had confronted, I became aware that I could not fight fate. To accept and to continue living were, in fact, the best ways to survive and love my life.

“Attention, please,” boomed the ship’s loudspeaker. “We have docked at Ambon. Those who end their trip here, please check your luggage and belongings. The stairs are located at the third dock to the right of the ship’s stern. Thank you!”

I helped Ri stand, buttoned his jacket, then picked him up. I shouldered the only bag we had, stuffed with our clothes.

We shuffled along slowly with the other people toward the stairs. I let my tears slide down my cheeks freely. Ri, with his clear, round eyes, hugged my neck tighter. A light drizzle made the harbor glisten. From the top of the stairs, I felt that the small-town lights at the foot of the high hills were welcoming me. Below, a sea of people, standing under hundreds of open umbrellas, waited to welcome their arriving friends and relatives.

I snatched off my jilbab and tossed it into the sea. The thin, black cloth slowly rode the wind until it landed on the water’s surface and disappeared.

I closed my eyes, inhaling the warm air that I had missed so unbearably. This is what it means to be home!

When I opened my eyes, Abu’s smiling face appeared like a vision in the twilight.

Goodbye, Abu. May your path be easy. Forgive me for not being able to uphold your trust and my devotion to you.

I wiped my tears and resituated Ri on my hip. Slowly, the two of us descended the steps, one by one.

*****