Past Stories

Merdeka Iman

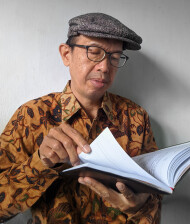

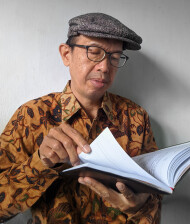

Aryl Timothy Madilah loves reading and learning about language. He studies translation at the English Literature Department, Faculty of Languages and Arts, at Satya Wacana Christian University.

Madilah has taught at the Pelangi Nusantara Course and Training Institute since 2023, and also teaches Indonesian for foreign speakers and English for high school students. He often writes fantasy-style stories on his Wattpad page and shares short poems on Instagram, @himthatlilomayday.

Aryl’s winning question: Does the story’s location actually exist and, if not what inspired you to create it? How and why did you choose which Indonesian words to translate and which Indonesian words not to translate for the English reader?

Aryl Timothy Madilah: timothymadilah024@gmail.com.

***

Merdeka Iman

Angin sepoi bertiup masuk dari jendela-jendela kelas, mengusir rasa gerah yang disebar oleh terik Magelang. Langit hari itu bersih dari awan meskipun Maret baru bersua, sehingga atap genting kelas itu tidak cukup untuk mencegah udara beringsang. Para murid di kelas itu baru selesai memberi salam serempak kepada Paulus, guru pelajaran agama, setelah jam pelajarannya berakhir. Dia beranjak dari meja guru, sementara para murid kembali duduk, merapikan meja, mengorek-ngorek isi tas, dan saling bercengkerama.

Paulus menghentikan langkahnya tepat di ambang pintu, lantas berbalik dan memanggil seorang murid. “Mardika!” Dengan alis mengernyit, bibir melengkung ke bawah, dan mata memicing, Paulus mencari sosok yang dia panggil. “Nanti ke ruang guru. Saya mau bicara denganmu.”

Perhatian para murid teralihkan sejenak. Ada yang menoleh ke arah Paulus, ada yang menoleh ke arah Mardika. Paulus kembali melangkah keluar dari kelas itu, sementara Mardika mengembuskan napas pelan, menatap lelah ke arah Paulus yang pergi meninggalkan kelas.

Bunyi lonceng berdentang keras, menggema mengisyaratkan jam istirahat.

***

Para murid berbondong-bondong keluar, menyapa semburat keemasan di luar kelas. Lapangan sekolah menjadi ramai oleh murid-murid yang lalu-lalang dengan tas di punggung mereka. Mardika berjalan menyusuri selasar dengan langkah lambat dan mata terpatri ke depan. Tidak menyadari ada Rahardian di belakangnya.

“Woi!”

Mardika tersentak kecil, punggungnya ditepuk sampai berbunyi halus. “Kaget!” Dia menoleh kesal pada Rahardian, pemuda yang kini berjalan beriringan di sebelah kanannya. “Kenapa?”

Rahardian tergelak. “Jalanmu kayak orang lesu. Gampang dibikin kaget.”

Mardika hanya menggeleng. “Kebiasaan.”

Rahardian menghela dan mengembuskan napas, meredakan tawanya. Dia merangkul Mardika sampai bahu Mardika oleng sedikit. “Pak Paulus bilang apa aja tadi? Aku tunggu kamu sampai istirahat selesai, kamu tidak muncul-muncul.”

“Biasa,” jawab Mardika. “Di mejanya di kantor guru, aku diceramahi panjang lebar soal nilai agamaku. Katanya aku tidak ada niat belajar, tidak ada keinginan berubah. Suaranya keras banget sampai guru-guru lain melirik-lirik ke meja kami. ‘Minggu depan sudah penilaian tengah semester, kamu mau nilaimu anjlok kayak semester lalu?’ Begitu katanya. Habis itu aku malah didoakan sama dia. Dimintakan tuntunan Roh Kudus.”

Rahardian kembali tertawa, keras tawanya mengundang mata beberapa murid di parkiran sekolah. “Memang ya, bapak kita itu. Kelakuan luarnya aja mendukung kepercayaan berbeda, padahal aslinya cari muka. Mana ada guru agama, guru agama Islam sekali pun, yang bacain ayat ke siswa di dalam ruang guru? Ngawur, sembarang.”

“Hus, Yan, banyak orang,” tegur Mardika.

Rahardian membalas dengan decak tak acuh. “Nggak salah, kok. Biar aja didengar orang.” Mereka sampai di pelataran parkir. “Ayo, cari makan dulu.”

Mardika mengernyit. “Belum makan?”

“Kamu ‘kan lama banget di sana tadi.” Rahardian menyodorkan helm candangan dan menyalakan motornya. “Ayo. Sembahyangmu masih lama, ‘kan?”

Mardika menggeleng, tidak percaya bahwa Rahardian sudah sabar menunggunya supaya mereka bisa makan bersama. “Ayo. Di tempat biasa ya?”

***

Lampu teras telah menyala temaram ketika Mardika tiba di depan rumah. Dia melakukan salam kepalan kepada Rahardian, mengucapkan terima kasih dan bilang sampai bertemu besok. Rahardian lantas melaju melewati jalan kecil berpenerangan remang-remang. Ketika Mardika memasuki halaman rumah, motor bebek hitam telah terparkir di kiri pintu pagar sebelah dalam, siap untuk dibawa keluar. Melihat itu Mardika buru-buru masuk ke dalam rumah.

“Sugeng dalu, Pak, selamat malam,” ucap Mardika ketika memasuki rumah. Dia menghampiri Hartono, ayahnya, yang sedang duduk di kursi ruang tamu. Mardika menyalami ayahnya dengan membungkuk dan menempelkan dahinya ke punggung tangan ayahnya.

“Sugeng bengi, selamat malam Nang,” balas ayahnya. “Kenapa baru pulang?”

“Tadi pergi makan sebentar, diajak Rahardian,” jawab Mardika halus. “Bapak sudah siap?” tanyanya, mengabaikan penampilan ayahnya yang sudah berpakaian rapi dengan lurik, kemeja coklat tua berlengan panjang dengan bujur garis hitam, dan blangkon, penutup kepala khas Jawa. Di sebelah ayahnya, juga ada bungkusan.

“Tinggal tunggu kamu.” Ayahnya berdeham sekali. “Mandi dulu sana. Mau sembahyang harus bersih.”

Mardika berjalan cepat menuju kamar, melepas tasnya, dan melesat ke kamar mandi. Setelah kira-kira lima menit berlalu dia sudah kembali ke kamar. Sesaat kemudian dia keluar dengan kemeja dan celana panjang serba hitam, menghampiri ayahnya yang sudah berdiri di ambang pintu dengan bungkusan di tangan.

“Astuti tidak ikut, Pak?” Mardika celingak-celinguk.

Dari bagian dalam rumah terdengar suara melengking menyahut, “Ogah!”

Ayahnya memejam.

Mardika menggelengkan kepala sambil menggumam, “Anak itu.”

“Sudah, sudah. Sudah makin malam, tidak baik berlama-lama,” putus ayahnya. Dia mengangkat bungkusan yang dipegangnya sampai setinggi dada Mardika. “Nang, pegang ini. Ayo kita pergi.”

Mardika menerima bungkusan itu, melangkah keluar rumah sembari menutup pintu dan menguncinya.

***

Mardika dan Hartono melintasi jalan setapak di antara kubur-kubur berkijing. Mereka kemudian berhenti di sisi sebuah kuburan dengan nisan kayu yang berterakan nama Watiningsih, ibu Mardika. Mardika membuka bungkusan yang berisi dupa, kemenyan, dan kantung kecil berisi kembang. Dia menaburkan kembang ke atas kuburan itu, sementara Hartono meletakkan dupa dan kemenyan di depan nisan. Sesudah menyalakan dupa dan kemenyan itu, keduanya bersimpuh. Mereka mengatupkan tangan, memejamkan mata, dan memanjatkan doa.

Dalam doanya untuk sang ibu, Mardika terbayang peristiwa tepat setahun lalu, ketika keluarganya berduka karena kepergian sang ibu. Hanya ada Pak RT dan sedikit warga yang membantu pemakaman waktu itu, karena pembatasan akibat wabah COVID masih diberlakukan. Namun yang lebih membekas di ingatannya adalah kenyataan bahwa ibunya dimakamkan menurut tata cara Islam. Semua warga yang menyempatkan diri membantu, yang jumlahnya bisa dihitung dengan jari, seluruhnya muslim.

Hati Mardika ngilu seakan ditusuk jarum tiap kali teringat akan hal itu. Orangtuanya adalah penghayat Kapribaden yang teguh, yang giat dalam menjalankan ajaran Romo Semono. Namun, keadaan memaksa mereka untuk melepas kepergian sang ibu dalam tata cara yang tidak mereka anut. Dalam doanya untuk sang ibu, Mardika menyisipkan permohonan pada Moho Suci, pada Tuhan, agar ketika ajal menjemput, ayahnya maupun dirinya dapat dimakamkan menurut tata cara penghayat Kapribaden.

Ketika Mardika membuka mata, dia mendapati ayahnya sedang merapikan barang yang mereka bawa. Walaupun raut muka Hartono datar, Mardika merasakan ada kelegaan yang terpancar dari wajah itu. Mardika ikut berdiri, memegang nisan kayu itu sesaat, kemudian melangkah mengekori ayahnya dalam diam.

“Bapak ya, Nang,” Hartono membuka percakapan, “dulu sebenarnya pengin Ibu disemayamkan menurut Kapribaden.”

“Hm.” Mardika membalas, antara terkejut dan tidak. Kepalanya sedikit menunduk mencoba mengatur langkah di jalan setapak yang berpenerangan remang-remang.

Hartono meneruskan. “Waktu itu memang susah. COVID bikin kita tidak bisa berbuat banyak, hanya bisa narimo, menerima dan ikhlas. Bapak, ya, Nang, bukannya tidak suka dibantu mereka. Toh caranya juga mirip dengan cara kita menyemayamkan orang meninggal.”

Iya, mirip, hati Mardika menyahut, tapi —

“Tapi rasanya Ibu seperti dijauhkan dari kita, Nang.” Hartono meneruskan suara hati Mardika.

“Iya, Pak.” Mardika kini menyuarakan isi hatinya. “Aku usahakan Bapak kelak enggak sampai seperti itu.”

Hartono terkekeh pelan. “Masa depan tidak ada yang tahu, Nang. Tapi yang paling penting kamu tetap teguh dengan kepercayaan kamu. Tetap dituntun Moho Suci untuk menggapai apa yang mau kamu gapai. Bapak bangga sama kamu, Nang, karena kamu tidak malu mewarisi apa yang Bapak-Ibumu ini percayai. Bapak yakin, nantinya orang-orang akan lebih terbuka lagi dengan orang-orang seperti kita ini.”

“Iya, Pak,” jawab Mardika.

Mardika berhenti sejenak ketika mereka sampai di gapura pekuburan. Dia menengadah, memandang bulan yang hampir berwujud separuh. Awan mendung perlahan menutupi langit, dan rasanya ada setitik air menyentuh pipinya. Mardika buru-buru menghampiri Hartono yang telah menyalakan motor.

***

Bekas hujan yang mengguyur basah Magelang malam itu hilang sama sekali pada keesokan harinya. Terik siang menembus rambut Mardika yang sedikit gondrong, membuat kepalanya kepanasan selagi dia dan Rahardian melintasi lapangan sekolah. Begitu sampai di selasar depan kelasnya, mereka berdua duduk di lantai.

“Panas banget, gila!” Rahardian mengeluh. “Lain kali jangan tinggalin bukumu di rumah.”

Mardika mengipasi tengkuknya dengan buku catatan yang baru saja mereka ambil dari rumahnya. “Ya maaf, kupikir udah masuk tas tadi pagi,” dalihnya. “Makasih udah pinjamin motor, ya.”

“Aman.” Rahardian mengangkat jempol, kemudian mengibas-ngibaskan kerah seragam batiknya. “Untung Pak Satpam baik, mau ngijinin tadi. Oh ya, catatan agamamu lengkap, ‘kan?”

Mardika berhenti mengipas, membuka-buka buku catatan yang dipakainya mengipasi tengkuk dan leher sedari tadi. “Lengkap, kok,” jawabnya yakin setelah memeriksa isi buku itu tiga kali. Dia lalu menoleh kepada Rahardian. “Terakhir yang Perdamaian dalam Budaya itu, ‘kan?”

Rahardian mengangguk. Kemudian dia terkekeh kecil, sepertinya tergelitik oleh sebuah ingatan yang menyelip muncul.

“Kok ketawa?” Mardika mengernyit.

“Enggak, jadi ingat aja,” ujar Rahardian. “Waktu itu ‘kan Pak Paulus bahas soal beriman lewat iman orang lain. Lucu aja, soalnya kelakuan beliau ke kamu itu justru nggak mencerminkan hal itu.”

Sontak Mardika memutar ingatan. Benar memang, waktu itu Paulus membahas banyak tentang bagaimana semangat tolong-menolong dan gotong-royong itu sudah ada di Indonesia sejak dulu kala. Beliau juga dengan penuh semangat menekankan bahwa semua itu adalah nilai Kristiani yang muncul dengan corak kedaerahan. Bagi beliau, itu adalah bukti kehadiran jiwa Kristiani di bumi pertiwi ini. Pendapat itu menggelikan bagi Mardika, mengingat semua contoh itu sudah lama ada sebelum agama Kristen masuk.

“Aku memang bukan Kristen taat ya,” Rahardian melanjutkan, “tapi bukannya contoh-contoh yang dikasih Pak Paulus itu semuanya lebih ke arah nilai budi pekerti ya? Artinya bukan cuma punya orang Kristen. Pendeta gerejaku kalau bahas soal itu juga selalu bilang, semua agama, semua kepercayaan itu punya nilai budi pekerti yang umum sifatnya, yang menuju pada kesejahteraan manusia.”

Mardika menyetujui. “Semua kepercayaan memang tujuannya untuk kesejahteraan manusia kok, tapi selain itu juga kesejahteraan manusia dengan dunia sekitarnya. Semua adat yang kami lakuin itu nggak cuma asal menyembah roh, apalagi setan. Aku pernah bilang ‘kan, kami mengajarkan untuk laku tresno welas lan asih marang opo lan sopo wae, mencintai dan berkasih sayang kepada apa dan siapa saja. Adat kami itu ya sama saja dengan ibadah yang dijalankan oleh para penganut agama.”

“Makanya. Beliau itu sebenarnya justru enggak menerapkan nilai-nilai yang beliau ajar kalau masih memandang rendah kamu. Katanya saja, ‘Kasihilah musuhmu,’ tapi ini murid sendiri kok tidak dikasihi,” rangkum Rahardian.

Mardika mengangguk, bersependapat. Tepat setelah itu dentang lonceng terdengar, mengisyaratkan para murid untuk kembali ke kelas.

***

Tiga hari telah berlalu sejak percakapan Mardika dengan Rahardian, tetapi Mardika masih bisa mendengar samar-samar perkataan Rahardian di telinganya. Apapun yang berurusan dengan kepercayaannya akan selalu meninggalkan bekas di jiwa Mardika. Buku catatan agama yang diterawanginya sedari petang turut menimbun gundah. Sekeras apapun Mardika mencoba mempelajari kisi-kisi ujian agama besok, gundah hatinya selalu mengganggu perhatiannya. Otak Mardika masih bergelut dengan kenyataan bahwa kebebasan iman belum juga bisa benar-benar dia rasakan.

Mardika merasa pelipisnya seperti ditusuki jarum. Dia memutuskan untuk berhenti sejenak. Dia melempar bukunya ke atas meja ruang tamu sampai menimbulkan bunyi kecil. Tepat pada saat itu, matanya menangkap sosok Astuti berjalan menuju pintu depan. “Mau ke mana, Dik?” Alisnya mengkerut mendapati adiknya berpakaian rapi dan santai, juga menyampirkan tas selempang kecil.

“Ikut temen, ke kota,” jawab Astuti tanpa menoleh pada Mardika.

Mardika menjeling ke arah gawainya yang menyala, memeriksa jam. Sudah pukul enam sore kurang sepuluh menit.

“Ikut ibadah bareng di gereja temenmu lagi?” Mardika menebak, samar-samar terdengar dengusnya.

“Iya, Mas,” Astuti menjawab, pendek dan datar. Tangannya membuka pintu, tetapi dia belum melangkah keluar. Dia menawarkan dengan suara malas, “Mau ikut?”

Mardika mengembuskan napas. “Enggak. Cuma tanya.” Dia heran juga dengan tawaran adiknya.

Astuti menggeleng kecil. “Anak muda itu ya bergaul toh, Mas. Bukan sibuk sembahyang aja.” Tangannya melepas pegangan pintu, merogoh ke dalam tas selempangnya dan mengeluarkan gawai.

Oh, anak ini …. Kernyitan heran Mardika berubah menjadi kernyitan jengkel. “Mulutmu itu ngawur banget, sembarangan. Keluar rumah itu pamit, bukan cari perkara.”

“Iya, iya. Pergi dulu, temenku udah sampai.” Astuti melangkah keluar, setengah tergesa.

“Hati-hati di jalan! Pulang nanti jangan kemalaman!” seru Mardika. Dia lalu berdiri, pergi menutup pintu yang ditinggalkan terbuka oleh Astuti.

“Ikut ibadah bareng temen cuma cari seru-serunya aja,” gumam Mardika sembari menutup pintu. “Ibadah macam apa itu. Dasar. Dikiranya sembahyang itu nggak guna, apa?” Mardika kembali duduk di kursi ruang tamu. Menatap penat buku catatannya.

Bagi Mardika, belajar untuk ujian itu bukanlah hal yang amat sulit. Hanya saja, dia selalu kehilangan minat setiap bertemu dengan pelajaran agama. Sedari sekolah dasar, nilainya di setiap ujian, dengan rentang nilai tertinggi seratus, tidak pernah melebihi tujuh puluh. Mardika tidak pernah puas dengan belajar agama orang lain; dia ingin merasakan belajar agamanya sendiri di sekolah.

Bukan berarti Mardika tidak diajarkan sama sekali tentang agama dan kepercayaan oleh ayahnya. Namun, Hartono memang lebih sering mengajarkan padanya berbagai ajaran dan cara hidup sebagai seorang penghayat Kapribaden. Mardika mempercayai dan melakukan semua itu dengan penuh keyakinan hingga kini, dan selalu merasakan kedamaian dengan melaksanakan ajaran-ajaran itu. Itulah yang membuatnya teguh pada kepercayaannya.

Namun Mardika rindu untuk mempelajari kepercayaannya, yang baginya adalah agamanya, dengan bebas di sekolah.

***

Hartono duduk menemani Mardika, setelah meminta izin dari kantor kepolisian tempatnya bertugas untuk mengikuti penerimaan hasil ujian anaknya. Keduanya duduk menghadap Paulus yang sedang memaparkan perolehan nilai Mardika. Siang itu langit penuh oleh awan kelabu.

Sepanjang pemaparan yang dilanjutkan penjelasan oleh Paulus, perhatian Mardika berkelana ke mana-mana. Otaknya enggan mendengarkan kata-kata wali kelasnya itu. Toh penjelasannya itu-itu terus, pikir Mardika, nilai-nilainya bagus tapi masih bisa ditingkatkan.

Ketika Paulus membahas pelajaran agama, Mardika tetap tidak acuh. Pelajaran itu selalu menjadi titik rendahnya, titik yang wajib dia tingkatkan. Telinganya sudah lelah dengan nasihat itu.

“Makanya saya jadi khawatir dengan perkembangan rohani anak Bapak,” ujar Paulus, menatap Hartono lekat-lekat sambil berdeham kecil.

Mardika yang menangkap perkataan itu seketika mengernyit tipis, melirik Paulus.

Hartono mengguratkan senyum kecil dan terkekeh singkat. “Bapak tidak usah khawatir soal itu. Saya selalu mengajarkan ihwal kerohanian pada Mardika juga kok di rumah, Pak,” jelasnya.

“Itu bagus, Pak Har,” tanggap Paulus, “tapi karena ini pelajaran Agama Kristen, saya sebenarnya berharap Mardika bisa belajar lebih giat juga untuk mendapat nilai yang memuaskan seperti di pelajaran lainnya.” Paulus mengunci kedua tangannya di atas meja. Matanya beralih sesaat ke arah Mardika.

“Iya, cuma memang nilai itu tidak betul-betul bisa dijadikan patokan ya, Pak,” balas Hartono.

Mardika tersenyum samar mendengar sanggahan lembut ayahnya.

“Justru itu salah, Pak Har.” Paulus menyanggah. “Nilai ini ‘kan capaian pemahaman, ya. Tapi pemahaman itu juga dilihat dari sikap dan kepribadian. Karena ini pelajaran agama Kristen, sepatutnya capaian siswa itu menunjukkan kalau dia mampu dalam hal hidup sebagaimana yang diajarkan.”

Tiba-tiba saja rasa gerah merayapi sekujur tubuh Mardika. Perutnya bergejolak, dadanya ngilu, kepalanya panas.

Hartono kembali terkekeh pendek. “Mardika ‘kan bukan Kristen, Pak.” Hartono halus mengingatkan sebelum melanjutkan, “Bisa dapat nilai segitu, walaupun agama itu bukan punya dia, buat saya memuaskan kok, Pak.”

Paulus menunduk, menggeleng pelan. “Bukan apa-apa, ya, Pak Har, cuma saya tetap menekankan capaian yang lebih baik lagi. Selama bersekolah di sini nilai agama Kristen Mardika selalu saja hanya rata-rata. Maka dari itu, pemahamannya tentang agama Kristen harus ditingkatkan, bukannya dibiarkan. Penghayat itu ‘kan juga menerapkan nilai-nilai Kristiani sebenarnya,” jelasnya.

Kepala Mardika kini terasa mendidih. Tangan kanannya mengepal di atas pahanya, sedikit gemetar. Kejengkelan yang menimbun ngilu di dadanya hampir mencapai lidah dan membuatnya ingin memuntahkan bantahan.

Hartono, masih menyambut penjelasan Paulus dengan senyum. Sudut matanya dapat melihat tangan Mardika yang mengepal. Diam-diam Hartono menggenggam kepalan Mardika. “Nanti saya bicarakan ke Mardika lagi, ya, Pak,” tutup Hartono.

Mardika mengatur napas pelan-pelan, mencoba menelan semua kejengkelannya.

Mardika dan Hartono berdiri. Mereka menyalami Paulus, kemudian beranjak pergi dari kelas itu. Mendung siang itu mulai menebarkan rintik-rintik ketika mereka pergi.

***

Sudah dua hari hujan dan gerimis bergantian tumpah mengguyur Magelang. Mardika duduk bersila di lantai kamarnya, ditemani suara rintik gerimis dan temaram lampu. Hawa senja nan sejuk yang mendekap Mardika membuatnya tenang. Matanya memejam, napasnya dalam dan teratur. Tangan kanannya lekat di depan ulu hati, dengan telapak menghadap ke kiri, sementara tangan kirinya berada di kiri tubuhnya, sedikit di bawah rusuk. Mardika bersembahyang, menumpahkan gundah dan kesalnya.

Dalam batinnya, Mardika mengingat kembali perkataan Paulus. Mardika merenungkan mengapa perkataan itu membuatnya begitu marah. Dia lantas mengingat semua perkataan, juga perlakuan yang pernah diterimanya. Mardika menarik napas dalam lalu mengembuskannya, ya mengembuskan semua beban hati itu keluar. Dia mengukuhkan keadaan batinnya dan menerima semua yang telah berlalu. Kemudian berdoa untuk keluarganya dan semua penghayat kepercayaan agar mampu manunggal, menyatu dengan Moho Suci.

Tepat ketika Mardika membuka mata menyelesaikan sembahyangnya, terdengar suara motor tiba. Mardika berdiri dan melangkah keluar kamar. Di teras dia mendapati Hartono sedang membuka jas hujan.

“Sugeng dalu, Pak, selamat malam,” sapa Mardika, menghampiri dan menyalami Hartono dengan menempelkan dahi ke punggung tangan ayahnya.

“Sugeng bengi, Nang,” balas Hartono. “Daerah Mungkid deras banget. Teman-teman pegiat yang lain tadi pengen nunggu di sekolah habis menanyakan soal pengadaan pelajaran buat penghayat, tapi Bapak nggak mau. Pengennya langsung balik, tidur.”

Keduanya berjalan ke dapur mendapati Astuti yang asyik makan di ruang makan sambil sesekali membuka gawainya.

“Sugeng bengi, Ndhuk. Lagi makan toh?” Hartono menyapa Astuti.

“Sugeng dalu, Pak. Iya,” balas Astuti ringkas.

“Gimana, Pak?” Mardika mengeluarkan semangkuk garang asem ayam dari lemari makan.

“Masih susah, Nang.” Hartono menyeduh air, kemudian mengambil dua piring dan dua sendok. “Waktu kami datangi, tiga minggu yang lalu, katanya permohonan untuk pengadaan mata pelajaran agama bagi penghayat sedang diurus.

“Sekarang mereka berkata, ‘Tidak bisa dilanjutkan. Harus menghadap dinas DIKBUD.’ Padahal waktu itu pengajar buat penghayat ada dan bareng kami, segala berkas juga sudah lengkap.” Hartono mematikan kompor, menuang air panas ke salah satu gelas, lalu mencampurnya dengan sedikit air dingin dan mengakhiri, “Kan menyusahkan begini ini.”

Mardika dan Hartono membawa semua makanan dan minuman itu ke ruang makan. Astuti beranjak ke dapur dengan piring kosong.

“Jadi masih belum bisa ada pelajaran penghayat di sekolah ya.” Mardika menyimpulkan. Dia memejam sesaat, komat-kamit berdoa, kemudian membuka mata dan mulai menyantap makanannya.

“Bisa, sebenarnya,” ujar Hartono, “cuma baru bisa sebagai pelajaran tambahan, bukan wajib.”

“Itu pun nggak masalah menurutku.” Mardika meyakinkan ayahnya.

Hartono menatap anaknya, tersenyum. “Nanti bakal bersurat lagi ke sekolahmu, mau bantu nganterin?”

Mardika ikut tersenyum. “Mau dong.”

“Mantap.” Hartono terkekeh singkat.

Mulai dari langkah kecil, batin Mardika. Hatinya mantap untuk mengusahakan kebebasan beragama yang selalu bergema lewat berita dan semboyan, di dunia nyata maupun dunia maya. Mardika bertekad membantu mengusahakan hadirnya pendidikan agama bagi penghayat kepercayaan, mulai dari sekolahnya. Mengumpulkan sesama murid yang juga penghayat kepercayaan di sekolahnya. Mardika ingin mendorong mereka untuk teguh dalam iman mereka sebagai penghayat dan menyuarakan hak mereka untuk merasakan kesetaraan dalam mengenyam pendidikan agama. Ramai-ramai bertemu dengan pihak sekolah, kalau harus, batin Mardika lagi, atau sekalian bawa pihak DIKBUD.

Mardika bertekad menggapai kebebasan beragama, beriman, atau berkepercayaan yang sesungguhnya. Mereka akan bebas mengamalkan kepercayaan masing-masing sesuai dengan hak hidup masyarakat merdeka.

*****

Freedom of Worship

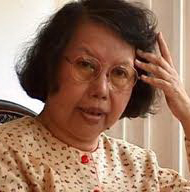

Yuni Utami Asih has loved poetry, short stories, and novels since elementary school. She stepped into the world of translation after hosting the launch of Footprints/Tapak Tilas (Dalang Publishing, 2023), a bilingual short story compilation in celebration of Dalang’s tenth anniversary. The first novel she translated was Pasola (Dalang Publishing 2024), by Maria Matildis Banda. Her most recent work was translating the 2025 series of six short stories to be published in installments on Dalang’s website.

Apart from teaching at the English Language Education Study Program, Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, Mulawaran University, Asih is involved in educational workshops for teachers in Samarinda, East Kalimantan, Indonesia, and surrounding areas.

Yuni Utami Asih: yuniutamiasih@fkip.unmul.ac.id.

****

Freedom of Worship

It was only early March, yet the skies were clear and the tiled roof couldn’t protect the school from the sultry heat gripping Magelang. The students had just said goodbye to Mr. Paulus, the religious studies teacher, after class had ended. Mr. Paulus left his desk while the students tidied theirs, chatting with one another and rummaging through their school bags.

At the classroom door, Mr. Paulus turned. “Mardika!” With furrowed brows and down-turned mouth, Mr. Paulus squinted, looking for the student he had called. “I want to talk to you at my desk in the teachers’ room.”

For a moment, the students’ attention was divided. Some turned to look at their teacher, others to look at Mardika. Mr. Paulus continued out of the classroom, while Mardika sighed and stared wearily at his teacher’s departing back.

The bell, signaling recess, rang loudly.

***

Students carrying backpacks poured out of the classrooms and into the golden sunshine, crowding the sidewalks surrounding the school. Looking straight ahead, Mardika walked slowly, unaware of those around him.

“Hey!” Someone tapped his shoulder.

Mardika let out a startled gasp. He turned irritably to Rahardian, the young man now walking beside him. “You scared me! What?”

Rahardian laughed. “You walk like you’re in a daze. It’s easy to scare you!”

Mardika shook his head. “Just a habit.”

Rahardian sighed, holding back his laughter. He shook Mardika’s shoulder lightly. “What did Pak Paulus say? I waited for you until recess was over, but you never showed up.”

“Just the usual,” Mardika replied. “He lectured me about my poor grade in religious studies. He said I don’t show any interest in learning, and I don’t seem motivated to change. He spoke so loud that other teachers looked over at our table! He reminded me that next week is the midterm, and did I want the same bad grade I had last semester. Then he prayed for me. He asked the Holy Spirit to guide me.”

Rahardian laughed so loud that some students in the parking lot turned to look them. “It seems his nature to act as if he supports different beliefs,” Rahardian chuckled, “but actually it’s just apple polishing. Have you ever seen any religion teacher, even a Muslim one, who reads verses to students in the teachers’ room? It’s crazy! It’s ridiculous!”

“Hush, Yan,” Mardika warned his friend. “There are a lot of people around.”

Rahardian shrugged. “I didn’t say anything wrong. I don’t care if people hear me.” They arrived at the parking lot, and Rahardian started his motorcycle. “Come on, let’s get something to eat.”

Mardika frowned. “Haven’t you eaten yet?”

“No, you were with Pak Paulus for so long. Come on. We still have time before it’s your prayer time, right?”

Mardika shook his head in disbelief. Rahardian waited for me just so we could eat together. “Let’s go!” he said. “The usual place, OK?”

***

The porch light shined dimly when Mardika arrived home, accompanied by the roar of Rahardian’s motorcycle. Mardika thanked him and said he would see him tomorrow. The two fist-bumped, then Rahardian roared off down the narrow, shadowy road.

As Mardika entered the yard, he noticed a black moped parked inside the gate, ready to go. He hurried into the house. “Sugeng dalu, good evening!” Mardika called out using the proper level of respectful Javanese. Hartono, his father, sat in a living room chair. Mardika bowed and rested his forehead against the back of his father’s hand.

“Sugeng bengi, good evening, Nang,” his father replied. “Son, why are you so late coming home?”

“Rahardian invited me to have dinner,” Mardika replied softly. “Are you ready?” He ignored the fact that his father was already neatly dressed in lurik, a dark-brown, long-sleeved shirt with black stripes, and blangkon, traditional Javanese headwear. Mardika noticed the bundle next to his father.

“Just waiting for you.” Mardika’s father cleared his throat. “Take a shower first. You must be clean for prayers.”

Mardika walked quickly to his room, dropped his school bag, and darted into the bathroom. He returned to his room in five minutes and dressed in a black shirt and trousers, then joined his father, who stood in the doorway holding the bundle.

“Is Astuti not coming?” Mardika asked, looking around.

“No!” came a shrill reply from inside the house.

Mardika’s father closed his eyes.

Mardika shook his head and muttered, “That child.”

“Just let it be,” his father said curtly. “It’s getting late. It’s not good to keep lingering,” He held out the bundle he was holding to Mardika. “Nang, please, carry it. Let’s go.”

Mardika took the bundle. After he and his father stepped out of the house, he closed the door and locked it.

***

Mardika and Hartono walked along the cemetery path between the tombs. They stopped beside a wooden grave marker bearing Mardika’s mother’s name, Watiningsih. Mardika untied the bundle, which held incense, frankincense, and a small bag of flowers. He sprinkled the flowers over the grave, while Hartono lit the incense and frankincense in front of the grave marker. Then the two knelt, clasped their hands, closed their eyes, and recited their prayers.

In the prayers for his mother, Mardika recalled the past year, in 2020, when his family mourned her passing. Only the village chief and a few neighbors had helped with the funeral because of the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. But what pained him more than anything was that his mother had been buried according to Islamic customs. The residents who helped could be counted on two hands. They were all Muslims.

Mardika’s heart ached every time he thought about it. His parents were staunch Kapribaden believers, who practiced the teachings of Romo Semono. Kapribaden was one of the region’s many local religious beliefs, passed down and practiced from generation to generation. These beliefs were not included in the “official religions” recognized by the government of Indonesia.

Circumstances had forced Mardika and his father to bury Watiningsih in a way different from their belief. In the prayer for his mother, Mardika inserted a request to Moho Suci, God, that when death came for his father and himself, they could be buried according to the Kapribaden tradition.

When Mardika opened his eyes, his father was tidying up the things they had brought. Although the expression on Hartono’s face was flat, Mardika felt a sense of relief radiating from it. Mardika rose, clasped the wooden grave marker for a moment, then silently followed his father.

“As for me, Nang,” Hartono opened the conversation, “I wanted to bury your mother according to Kapribaden custom.”

“Mmm.” Unsure about his feelings, Mardika kept his head down and focused on placing his feet carefully on the dimly lit path.

“It was a difficult time,” Hartono continued. “COVID kept us from doing much. We could only narimo, accept, and be strong. It’s not that I didn’t appreciate the help to bury her during that time. After all, the way they bury their dead is similar to ours.”

Yes, it’s similar, Mardika thought, but –

“But it feels like Ibu has been removed from us, Nang.” Hartono finished Mardika’s thoughts.

Mardika now spoke up. “Yes, Pak. I’ll make sure this doesn’t happen to you.”

Hartono chuckled softly. “No one knows the future, Nang. But the most important thing is that you stay true to your beliefs. Stay guided by the Holy Moho to achieve what you want to achieve. I’m proud of you, Son, because you’re not ashamed to practice what your parents believe in. I’m sure others will become more accepting of people with beliefs like us in the future.”

“Yes, Pak.”

Mardika paused when they reached the gate of the cemetery. He looked up at the halfmoon. As gray clouds slowly covered the sky, he felt a drop of water touch his cheek. Mardika hurried to join Hartono, who had started the moped.

***

All traces of the rain that soaked Magelang that night were completely gone the next day. The afternoon heat penetrated Mardika’s medium-long hair, and his head felt hot as he and Rahardian crossed the school grounds. When they arrived at the walkway in front of their classroom, they both dropped to sit on the floor.

“It’s so hot, it’s crazy!” Rahardian complained. “Please don’t forget your books at home anymore!”

Mardika fanned the back of his neck with the notebook they had just fetched from his house. “I’m sorry, I thought it was in my bag this morning,” he said. “Thanks for lending me the motorcycle.”

“Don’t worry.” Rahardian gave a thumbs-up, then loosened the collar of his batik uniform. “It’s a good thing the security guard was kind enough to let us go. So, did you finish your notes for the religious studies class?”

Mardika flipped through the notebook he had been fanning himself with. “Yes,” he replied confidently. After checking the contents of the page three times, he turned to Rahardian. “The last lesson is on Peace in Culture, right?”

Rahardian nodded, then chuckled, as if suddenly remembering something.

Mardika frowned. “Why are you laughing?”

“Nothing,” Rahardian said. “I just remembered Pak Paulus talked about practicing one’s faith through other people’s. It’s funny, his behavior towards you doesn’t reflect that opinion.”

Mardika raked his memory. Pak Paulus always talked a lot about the spirit of helping and the mutual cooperation that had long existed in Indonesia. He passionately emphasized that these Christian values had blended with regional cultural conduct. This to Pak Paulus proved the presence of Christianity in Indonesia. Mardika thought Pak Paulus ridiculous, because all examples he had mentioned, had prevailed long before Christianity was established.

“I’m not a devout Christian,” Rahardian continued, “but don’t the examples Pak Paulus gave mainly address ethical values? That means it’s not just meant for Christians; it’s meant for everyone. My pastor always says that all religions and beliefs have ethical values that are general in nature and lead to human welfare.”

Mardika agreed. “All religions and beliefs are not only for human welfare, but also for the harmony between people and their environment. All the Kapribaden customs we practice are not just randomly meant to worship spirits, let alone demons. I’ve told you before, the Kapribadens teach to practice tresno welas lan asih marang opo lan sopo wae: love and compassion for everything and everyone. Our customs are the same as the practices of other religious believers.”

“That’s why I think Pak Paulus doesn’t apply the values he teaches if he still looks down on you,” said Rahardian. “Pak Paulus told us, ‘Love your enemies,’ but he doesn’t even love his own students.”

Mardika nodded just as the bell rang, directing students back to class.

***

Three days had passed since Mardika’s conversation with Rahardian, but Mardika could still hear his friend’s words. Mardika always remembered everything that dealt with his beliefs. The notebook of religious studies he had been poring over since early afternoon was also weighing on his mind. No matter how hard Mardika tried to study for the upcoming religious study exams, his anxiety always interfered with his attention. He kept struggling with the fact that he had never felt the freedom of worship.

Mardika’s temples throbbed. He decided to take a break. He tossed the book on the living room table, where it landed with a light thud. He saw Astuti walking towards the front door. “Where are you going?” he asked, frowning when he noticed his little sister was dressed to go out and carried a small sling bag.

“To the city, with a friend,” Astuti replied without turning to her brother.

Mardika glanced at his glowing cellphone, checking the time. It was ten minutes till six in the early evening. “Going to a Christian church with your friends again?” Mardika scowled.

“Yes,” Astuti replied curtly. Opening the door, she asked, “Do you want to come?”

“No, I don’t. Just asking.” Mardika sighed. His sister’s invitation surprised him.

Astuti shook her head. “Young people need to socialize, not just pray.” She let go of the door handle, reached into her sling bag, and pulled out her phone.

Oh, that child … Mardika’s look of disbelief turned into annoyance. “Watch your mouth! You’re supposed to say goodbye properly when you leave the house, not look for an argument!”

“OK, OK. I gotta go; my friend is here.” Astuti hurried out, leaving the door open behind her.

“Take care!” Mardika called after her. “Don’t come home too late!” He closed the door.

“Joining friends for worship is just socializing for fun,” Mardika muttered. “What kind of worship is that? Youth. Does she think praying is useless?” Mardika sat back down on the living room chair and stared wearily at his notebook.

For Mardika, studying for exams was not difficult, unless he had to study religion. He always lost interest. Ever since elementary school, his score on every religious studies exam never exceeded seventy out of one hundred. He just wasn’t interested in learning someone else’s religion; he wanted to learn about his own Kapribaden religion at school.

It was not that his father did not teach Mardika anything about other religions and beliefs. It was just that Hartono more often educated him about the many ways of life as a Kapribaden believer. Until now, Mardika had always accepted and practiced those teachings with conviction. He felt peaceful when he performed the rituals that grounded him in his beliefs. Mardika longed to learn more about his Kapribaden faith — his religion — freely at school.

***

Hartono obtained permission from the police station where he worked to attend the parent-teacher meeting. He now sat with Mardika, facing Mr. Paulus, who was explaining Mardika’s scores. Outside, gray clouds filled the sky.

Throughout Mr. Paulus’s presentation, Mardika’s attention wandered. His brain refused to listen to his homeroom teacher. After all, the explanations are always the same, Mardika thought. My grades are good but could still be improved. When Mr. Paulus discussed religious studies, Mardika remained indifferent. It was always his low point, the academic area he needed to improve on. He was tired of the same advice.

“That’s why I’m so worried about your son’s spiritual development.” Mr. Paulus cleared his throat and looked intently at Hartono.

Mardika, who caught the words, frowned slightly, glancing at his teacher. Hartono quirked a small smile and chuckled. “You don’t have to worry about that,” he said. “I teach Mardika about spirituality at home.”

“That’s good, Mr. Har,” Paulus responded, “but since this is a Christian religious studies class, I hope Mardika can study harder to get the same satisfactory grades he manages for other subjects.” Mr. Paulus folded his hands together on the table and glanced momentarily at Mardika.

“Yes, but grades can’t really be used as a benchmark,” Hartono replied.

Mardika smiled faintly at his father’s gentle rebuttal.

“That’s exactly what’s wrong, Mr. Har,” Mr. Paulus countered. “Grades do indeed represent the value of an achievement or understanding. But understanding can also be measured in one’s attitude and demeanor. Since we are addressing Christianity, the student’s achievement should also show that he is capable of living as taught.”

Suddenly, Mardika’s whole body felt hot. His stomach churned, his chest tightened, his head ached.

Hartono gave another short chuckle. “Mardika is not a Christian,” Hartono subtly reminded Mr. Paulus. “The grade my son received, despite the fact that Christianity is not his religion, is good enough for me.”

Mr. Paulus looked down, shaking his head slowly. “No offense, Mr. Har, it’s just that I have to insist on better achievements. Mardika’s grades in religious studies have always been average. Therefore, his understanding of Christianity must be improved, not ignored. The Kapribaden believers also apply Christian values.”

Mardika’s head now throbbed painfully. His trembling hand clenched his thigh. The indignation building up in his chest was about to reach his tongue and spew out an angry rebuttal.

Hartono, however, continued responding to Mr. Paulus with a smile. From the corner of his eye, Hartono saw his son’s clenched fist and quietly grasped it. “I’ll talk to Mardika again later,” Hartono said.

Trying to swallow all his aggravation, Mardika breathed slowly. Father and son rose and shook hands with Mr. Paulus. As they left the room, it started to rain.

***

For two days, Magelang was drenched in rain. Mardika sat cross-legged on the floor of his room, accompanied by the pattering rain and dim lights. The cool twilight air embraced Mardika and calmed him. He closed his eyes and breathed, deep and regular. He placed his right hand against his breastbone with his palm facing left, while his left hand rested, palm up, against his waist. In this traditional position, Mardika prayed, pouring out his frustration and irritations.

Mardika recalled his teacher’s words. He remembered all the scoldings and the treatment he had received. He pondered why those words made him so angry. Mardika exhaled another deep breath, slowly releasing all his burdens. He accepted all that had passed and centered himself. Then he prayed for his family and all Kapribaden believers to merge with Moho Suci.

Just as Mardika finished his prayer and opened his eyes, he heard a motorcycle pull up to the house. Mardika stepped out of the room. On the porch, Hartono was taking off his raincoat.

“Sugeng dalu, good evening.” Mardika placed his forehead against the back of his father’s hand.

“Sugeng bengi, Nang,” Hartono replied. “It was raining heavily in the Mungkid area. The other advocates wanted to wait at the school after asking about the provision to add Kapribaden to the religious studies curriculum, but I didn’t want to. I wanted to go straight back to bed.”

The two of them walked into the dining room, where Astuti was eating while occasionally glancing at her cellphone.

“Sugeng bengi, Ndhuk,” Hartono greeted his daughter. “What are you eating?”

“Sugeng dalu, Pak.” Astuti replied briefly.

“How did it go?” Mardika asked his father, as he took a serving bowl of ayam garang asem, spicy coconut chicken stew, from the food cupboard.

“It is still difficult, Nang.” Hartono boiled some water, then took two plates and two spoons. “When we visited the school three weeks ago, the teacher for Kapribaden was with us, and all the paperwork had been completed. We were told that the application for the provision to teach the Kapribaden religion in school was being processed. But now they say we can’t continue. We have to go to the Office of Education and Culture.” Hartono turned off the stove, poured hot water into a glass, then mixed it with a little cold. “It’s troublesome.”

When Mardika and Hartono carried their dinner into the dining room, Astuti took her empty plate to the kitchen.

“So Kapribaden still won’t be taught at school.” Mardika briefly closed his eyes, mumbled a prayer, then started eating.

“It can be taught, actually,” Hartono said, “but only as an elective, not as a compulsory subject.”

“That’s fine with me, too,” Mardika assured his father.

Hartono looked at his son, smiling. “Would you like to help me when I write to your school?”

Mardika returned his smile. “I will.”

Start with small steps, Mardika thought. He was determined to work for the religious freedom that was always being broadcast through news and slogans. in the real and virtual worlds. Mardika planned to tenaciously promote the freedom of religious education, starting from his school. He wanted to gather fellow students who were also Kapribaden believers and encourage them to be firm in their faith, and to voice their right to be treated equally in receiving religious education. If necessary, we’ll meet with the school management, Mardika thought, and at the same time meet the authorities at the Education and Culture Office.

Mardika was determined to achieve true freedom in any religious expression. Everyone should be free to practice their respective beliefs in accordance with the right to live in an independent, free society.

*****

Kain Tapis Mak Unyan

Jauza Imani, a mother of two boys, has actively written since 2016. Her writings include several collections of short stories, children’s stories, and poetry.

Piknikita (Basabasi Publisher, 2021) is a collection of poems Imani wrote in collaboration with poet Kurnia Effendi. The children’s story Cerita Pertama Untuk Rara was self-published in September 2021 through Epigraf Publisher. In 2017, Imani also self-published a poetry collection, Hujan Kau Selalu Begitu, through Gong Publishing.

Siger Nunu Ketinggalan was named one of the five best short stories in Tak Kenal Maka Tak Indonesia, the Children’s Story Competition held by Toonesia x IKSI in 2022.

Imani is currently active in the Lampung Arts Council and is a member of several other literary groups, including: the Indonesian Female Poets; the Nulis Aja Dulu Community; Dapur Sastra Jakarta; and Hari Puisi Indonesia.

Imani’s winning question: What method do you use to capture the essence of an incident in a way that captivates the reader?

Jauza Imani: nurhikmah.imani126@gmail.com.

****

Kain Tapis Mak Unyan

Berita tentang hilangnya kain tapis di Pekon Way Sindi membuat desa di Kabupaten Pesisir Barat, Provinsi Lampung itu geger! Berita itu bukan sekadar berita biasa. Kain tapis itu akan digunakan sebagai penutup jenazah Mak Unyan, dukun beranak desa itu yang meninggal dunia pada dini hari.

“Di dipa tapis seno?” Terdengar suara Masri yang menggelegar di tengah suasana duka. Lelaki tua berperawakan kurus tinggi itu menanyakan keberadaan kain tapis milik Mak Unyan yang dibuat saat istrinya itu masih remaja. “Khadu kusegok ko, tibungkus dilom lemari!” Dalam logat bahasa Lampung yang kental, Masri seolah-olah berbicara kepada semua pelayat yang hadir di rumahnya. Dia merasa sudah membungkus dan menyimpan kain itu dalam lemari.

Tangan Masri bergetar saat mengaduk-aduk isi lemari kayu yang sudah reyot dimakan usia. Pakaian sederhana milik Mak Unyan berserakan di lantai. Baju dan celana panjang miliknya pun ikut terjelempah. Masri penasaran karena baru dua minggu lalu dia merapikan lemari bersama Mak Unyan usai salat Subuh berjamaah di rumah.

***

Masri masih ingat betul saat istrinya mengeluarkan bungkusan kain tapis itu dan menunjukkan kepadanya. Seolah-olah pertanda bahwa kain itu hendak digunakannya dalam waktu dekat.

Terdengar kembali pertanyaan Mak Unyan, “Sudah berapa puluh tahun usia tapis ini, ya?” yang dijawabnya sendiri, “Lupa, saya.” Tangannya yang renta merentangkan satu-satunya kain yang dia banggakan. Setidaknya, dengan kain tapis itu dia bangga dilahirkan sebagai gadis Lampung.

Pikiran Masri sekadar menerawang ke saat itu. “Ai, nah! Lupa juga, saya!” timpalnya sambil tertawa kecil memperlihatkan gigi ompongnya. Gigi sampingnya di kanan dan kiri tampak jelas sesaat dia lanjut, “Waktu itu kamu sikop nihan!” Masri teringat memuji istrinya yang cantik jelita di saat hari bahagia mereka. “Saya tunggu kamu sampai selesai membuat tapis itu. Biar bisa saya lamar. Dan, kamu memakainya saat pernikahan kita.”

Larut dalam kenangan, Masri mendekati Mak Unyan yang saat itu duduk di ranjang besi peninggalan neneknya. Bentangan kain tapis masih di pangkuan istrinya. Masri ikut memegang ujung kain tapis itu. Warna benang emasnya belum memudar. Hasil sulaman tangan Unyan – sangat rapat dan rapi sesuai dengan sifatnya yang rajin dan telaten, apalagi dalam merawat bayi. Pantas saja dia menjadi dukun beranak yang terkenal. Dalam hati, Masri mengucap syukur bisa mempersunting Unyan yang menjadi rebutan pemuda-pemuda sebaya di kampungnya sekian tahun yang lalu.

Di benak Masri muncul kembali secara jelas Mak Unyan yang tersenyum bahagia karena dia masih ingat kisah kain tapis itu dan pernikahan mereka. Ingatan Masri melayang ke masa lalu. Usai akad nikah dinyatakan sah oleh para saksi barulah Unyan keluar dari kamar. Semua mata memandang ke arahnya dengan decak kagum. Kecantikan istrinya menjadi sempurna karena dia mengenakan kain tapis yang indah ⸺ susunan benang emasnya rapat dan halus serta berkilau memukau ⸺ hasil sulamannya sendiri.

Masri teringat Mak Unyan yang masih saja tersipu bila dibilang cantik olehnya. Saat itu, kedua tangan yang digunakan Mak Unyan untuk membantu persalinan sebagai dukun beranak di pekon Way Sindi, menutupi wajahnya yang bersemu merah. Semua guratan berebut tampil di wajahnya yang kini tidak berdaging lagi seperti dahulu. Masri mengundang kembali dan mempertahankan kenangan itu.

“Selamat, ya! Anakmu perempuan.” Ucapan seusai membantu persalinan seorang warga itu selalu dilanjutkan dengan pesan khas Mak Unyan. “Dang lupa, sanak muleimu ditawaiko napis!” Dia selalu mengingatkan warga yang ditolongnya untuk mengajari anak gadisnya membuat tapis.

Bagi masyarakat adat Lampung di kampung mereka, membuat kain tapis adalah keharusan. Sejak kecil, sepulang sekolah, selain mengaji, anak-anak perempuan belajar menenun dan menyulam kain yang berbentuk sarung itu dengan benang emas atau benang perak. Coraknya pun beragam. Di antaranya adalah Raja Medal yang menampilkan pernak-pernik berbentuk manusia; Laut Linau yang menunjukkan kupu-kupu; dan Tapis Inuh yang terpengaruh oleh hal-hal tersangkut dengan laut.

Masri yakin, tentu saja Unyan tidak akan lupa dengan tata cara menapis yang merupakan peninggalan leluhur ratusan tahun lalu. Tapis Inuh yang dipilihnya terpengaruh oleh lingkungan sekitarnya yang akrab dengan laut, misalnya, kapal, rumput laut, dan hewan laut. Meski penyelesaian membuat kain tapis itu memakan waktu berbulan-bulan, Unyan dan perempuan lain di kampungnya tetap bersabar bahkan seakan berlomba merampungkannya. Kelak, saat hari pernikahan mereka tiba, kain tapis itu akan dipakainya sebagai seorang pengantin. Demikian juga saat kematian datang, sebagai penghargaan dan penghormatan terakhir, kain tapis itu pula yang akan digunakan untuk menutup jenazahnya.

***

Masri masih mencari kain tapis Mak Unyan. Kini pencarian berpindah ke lemari di kamar Bayan, anak lelaki semata wayang yang hingga kini belum menikah. Mekhanai Tuha. Selama ini Bayan tidak tertarik dengan gadis-gadis di desanya. Katanya, dia tidak menemukan seorang mulei yang sepandai ibunya dalam hal membuat tapis. Konon, hasil sulam tapis seorang perempuan bisa menunjukkan sifat sang pembuatnya, apakah dia seorang yang penyabar, penyayang, pemarah, rajin, pemalas, atau yang lainnya.

Ada satu gadis yang paling dewasa umurnya di antara mereka. Gadis itu, Suri namanya, terkenal paling lamban dalam menapis. Bahkan Suri tertinggal jauh oleh penapis-penapis di bawah usianya. Sudah lama dia menaruh hati kepada Bayan. Meski lambat, lantaran berharap barangkali saja Bayan berkenan melamarnya, dia berusaha menyelesaikan tapisnya. Namun, Bayan tidak mengacuhkannya.

Sambil melihat ayahnya mencari kain tapis di lemarinya, Bayan teringat saat Mak Unyan bertanya, “Kapan kamu menikah, Bayan?”

Bayan memahami perasaan ibunya yang sudah tua. Pasti, dia ingin mendampingi anaknya hingga ke pelaminan dan mewariskan kain tapis buatannya kepada menantu dan cucunya kelak, andai dia sudah tiada.

“Nantilah, Mak,” Bayan teringat dia menjawab pelan saat itu.

“Mak khadu tuha,” terngiang di kuping Bayan ucapan ibunya yang lirih. Karena tidak ingin melukai hati ibunya, saat itu Bayan hanya terdiam. Sedangkan, ibunya seakan-akan memberi restu dengan berkata, “Suri anak baik, lajulah! Mak lihat dia menapis Inuh juga seperti Mak,”

“Jangan paksa Bayan, Mak,” Bayan ingat kembali ketika membujuk pelan ibunya seraya melangkah meninggalkannya.

“Bukan memaksa. Kekalau kalian berjodoh!” Suara ibunya yang berandai-andai, sayup-sayup masih terdengar di telinga Bayan.

***

Berita meninggalnya Mak Unyan dan hilangnya kain tapisnya menyebar cepat terbawa angin. Para tetangga dan kerabat yang datang selain sebagai pelayat juga ingin membuktikan kebenaran berita itu. Mereka seolah-olah berebut cepat datang untuk berbelasungkawa sekaligus menaruh tanda kasih. Mereka agaknya juga mencari bahan cerita.

Sebagian besar pelayat pasti tidak percaya dengan pemandangan di depan matanya – jenazah Mak Unyan tanpa kain tapis. Hampir tidak mungkin perempuan yang telah menikah tidak memiliki tapis buatannya sendiri. Apalagi Mak Unyan yang sesekali terlihat mendatangi gadis-gadis yang sedang menapis selama ini dikenal sebagai orang yang cerewet mengingatkan akan pentingnya anak gadis membuat tapis.

Detak jam dinding di ruang tamu tidak pernah berhenti. Namun, bagi Bayan kehidupannya seakan-akan sudah berakhir. Dia berduka kehilangan ibunya. Terbayang hari-hari indah bersamanya. Namun, suara ayahnya yang menggelegar menyadarkannya dari lamunan panjang.

“Bayan! Niku pandai di dipa tapis seno?” tanya Masri kepada Bayan, memastikan tahu tidaknya Bayan tentang keberadaan tapis Mak Unyan. “Ngeliak tapis seno, mawat?” tanya Masri, memastikan sekali lagi.

“Nyak mak pandai,” jawab Bayan. Suara lemahnya berusaha meyakinkan ayahnya bahwa dia tidak tahu. Pikirannya yang sedang kalut memaksanya berkata bohong kepada ayahnya di depan jenazah ibunya. Keributan yang ditimbulkan oleh lenyapnya kain tapis itu kini menyadarkannya betapa pentingnya benda itu bagi keluarga dan masyarakat adat di kampungnya.

Rumah panggung itu kian ramai didatangi tetangga. Pasangan sandal berjajar di anak tangga pertama dan kedua bagian bawah. Meski angin berembus dari sela-sela susunan kayu, ruangan itu terasa gerah karena banyak orang.

Masri membuka satu dari dua daun jendela lebar di sisi kanan ruangan. Dia sejenak memandangi kebun rambutan di samping rumah. Dengan begitu dia dapat menyembunyikan mata merahnya dari pandangan orang-orang. Dia berusaha menjinakkan gemuruh di dadanya yang menderanya sejak diketahuinya kain Mak Unyan tidak ada di lemari. Suara ayam jago berkeruyuk semakin jelas terdengar. Masri mendengarnya seperti celoteh cibiran yang dilagukan.

“Bayan, coba kamu pinjam saja tapis milik kerabat. Tidak apa. Usahakan agar ibumu bertapis, setidaknya sesaat sebelum dimakamkan, sebagai bentuk penghormatan kepada almarhumah,” bisik seorang pengtuha, orang yang dituakan di pekon Way Sindi, kepada Bayan. Sang pengtuha itu tidak ingin pelayat yang mestinya berduka malah bergunjing tentang hilangnya tapis Mak Unyan.

Di saat Bayan mengangguk menyetujui saran sang pengtuha, Suri datang bersama keluarganya. Mendengar kabar hilangnya tapis Mak Unyan, Suri, yang rumahnya tidak jauh dari rumah Mak Unyan, teringat kebaikan Mak Unyan selama ini sebagai tetangga dekatnya. Suri meminta izin kepada keluarganya dan bergegas kembali ke rumahnya. Dia berniat untuk meminjamkan kain tapis yang baru saja diselesaikannya.

“Nerima nihan, Suri.” Bayan mengucapkan terima kasih dan menerima kain tapis dari tangan Suri. Pandangan mereka sesaat bertemu. Bayan sempat melihat kesungguhan di mata Suri. Bayan seakan menemukan bukti dari kata-kata ibunya kala itu. Benar, Suri adalah perempuan yang baik.

“Jejama, dengan senang hati,” jawab Suri pelan tetapi hangat. Baru saat itulah dia bertatapan langsung dengan Bayan. Suri merasakan jantungnya berdegup lebih cepat. Dalam hatinya dia bertanya, mengapa selama ini, laki-laki yang berada di hadapannya itu, begitu acuh kepadanya? Dengan sedikit kikuk Suri membantu melepas ikatan pada bungkusan kain itu dan membiarkan Bayan yang membentangkannya.

Bayan mengganti kain panjang yang menutupi jenazah Mak Unyan dengan kain tapis milik Suri, perempuan yang pernah dipuji ibunya, tetapi selama ini tidak dia pedulikan. Ada rasa sesal menyusup di hatinya yang sedang berduka. Sementara itu, Suri tampak ikhlas kain tapisnya digunakan pertama kali untuk kematian Mak Unyan, bukan di hari pernikahan dirinya. Rasa haru pun diam-diam menyelinap di hati Suri.

Suasana duka dan khidmat berlangsung di ujung persemayaman jenazah Mak Unyan. Sejak tadi di rumah kayu itu ayat-ayat Alquran dilantunkan. Sesekali terdengar isak tangis dari beberapa pelayat yang datang bercampur dengan bisik-bisik tentang Suri dan Bayan.

Masri berhenti mencari kain tapis Mak Unyan ketika dilihatnya jenazah istrinya sudah tertutup tapis. Meski demikian, amarah di wajahnya sulit disembunyikan. Di antara sedih dan kesal dia mencoba bersabar sambil menerima uluran tangan pelayat yang turut berbelasungkawa.

Bayan terduduk lemas di samping jenazah ibunya. Dia tidak sanggup berdiri menegakkan badan untuk memberi penghormatan kepada para pelayat yang masih berdatangan. Ingatannya melayang kepada perempuan bule yang dia temui di Pulau Pisang seminggu lalu.

“Sarrah.” Suara perempuan bule itu masih terngiang-ngiang di telinga Bayan saat dia menyebutkan namanya dan menjabat tangan Bayan. Kecantikannya membuat Bayan terpukau dan tidak bisa melupakannya. Wisatawan dari Australia yang baru saja dikenalnya itu berbicara banyak tentang indahnya kebudayaan Indonesia. Salah satunya adalah kain tapis, warisan budaya takbenda dari Lampung. Dia sengaja datang ke Indonesia, khususnya ke Provinsi Lampung, untuk mengadakan penelitian tentang tapis dan menuliskannya.

“Saya datang ke sini untuk melihat kain tapis,” ujar Sarrah saat itu dengan bersemangat meski terbata karena menggunakan bahasa Indonesia. “Saya dengar kain tapis yang dibuat di desa ini terkenal karena sulamnya rapi dan coraknya indah,” lanjutnya.

“Betul sekali!” ucap Bayan dengan bangga. Dia merasa bisa membuktikannya. Dia melihat sendiri bagaimana indahnya kain tapis yang dibuat oleh gadis-gadis di desanya. Apalagi kain tapis milik ibunya.

***

Sekarang, sambil duduk di samping jenazah ibunya, Bayan mengutuk dirinya sendiri. Berkali-kali dia mengusap wajah dan kepalanya. Dia seperti melihat ratusan gulungan benang emas. Bahan untuk menyulam kain tapis itu menari-nari mengelilinginya. Wajah ibunya yang sudah tertutup rapat di sampingnya pun tampak di pelupuk mata.

Bayan menyesali tindakannya yang gegabah tanpa berpikir panjang. Kini, meski jenazah ibunya sudah ditutupi oleh kain tapis milik Suri, tetapi hati Bayan justru semakin galau. Dia membayangkan ibunya yang bersusah-payah membuat kain tapis. Namun, di akhir hidupnya, kain itu malah tidak bisa digunakan untuk dirinya sendiri. Bayan tiba-tiba beranjak dari tempat duduknya menuju pintu.

“Bayan! Bayan! Haga dipa?” Suara-suara para pelayat yang menanyakan dia hendak ke mana, tidak dihiraukannya – termasuk panggilan ayahnya dan Suri. Bayan mula-mula melangkah cepat, kemudian berlari dan terus berlari menembus semak belukar. Hatinya berteriak dalam kebimbangannya.

Bayan tahu harus ke mana dia menuju, ya, ke arah pondok kecil tidak jauh dari pantai yang jendelanya menghadap ke laut. Jarak sekira tiga kilometer itu berusaha ditempuhnya dengan melalui jalanan tidak biasa agar tidak terlihat orang. Dia harus mendapatkan kembali kain tapis milik ibunya, sebelum jenazah Mak Unyan terlanjur dibawa ke luar rumah untuk dikebumikan.

*****

Mak Unyan’s Tapis

Yuni Utami Asih has loved poetry, short stories, and novels since elementary school. She stepped into the world of translation after hosting the launch of Footprints/Tapak Tilas (Dalang Publishing, 2023), a bilingual short story compilation in celebration of Dalang’s tenth anniversary. The first novel she translated was Pasola (Dalang Publishing 2024), by Maria Matildis Banda. Her most recent work was translating the 2025 series of six short stories to be published in installments on Dalang’s website.

Apart from teaching at the English Language Education Study Program, Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, Mulawaran University, Asih is involved in educational workshops for teachers in Samarinda, East Kalimantan, Indonesia, and surrounding areas.

Yuni Utami Asih: yuniutamiasih@fkip.unmul.ac.id.

****

Mak Unyan’s Tapis

News of the disappearance of Mak Unyan’s tapis in Way Sindi sent the village in the West Pesisir Regency of the Lampung Province into an uproar. It was not just any news. The hand-woven cloth, traditionally embroidered with gold and silver thread was to be used to cover the body of the village’s old traditional midwife, Mother Unyan, who had passed away in the early hours of the morning.

“Where is the tapis?” Old Masri’s booming voice cut through the thick, grieving atmosphere. The tall, thin man wanted to know the whereabouts of his wife’s tapis — the cloth she had woven and embroidered with gold thread when she was a teenager. “Khadu kusegok ko, tibungkus dilom lemari!” In his thick Lampung accent, Masri addressed all the mourners in his house. He was certain he had wrapped and stored the cloth in the dresser that he and his wife shared.

Masri’s hands shook as he again rummaged through the contents of the rickety wooden dresser. His wife’s simple wardrobe lay scattered on the floor. Masri’s own shirts and trousers were among them. Masri was baffled. Only two weeks ago, he and Mak Unyan had tidied up the dresser after performing the dawn prayer together at home. The tapis had been there.

Masri vividly remembered his wife taking out the tapis and showing it to him, as if she were going to wear it soon. He heard Mak Unyan’s question: “How old is this tapis, huh?” only to answer herself, “I forget.” Her frail hands had unfolded and held up the only cloth she was proud of. The tapis showed her pride to have been born a Lampung girl.

“Ai, nah! I don’t remember either!” Masri had replied with a chuckle, exposing his toothless gums. His remaining teeth gleamed as he continued, “You were sikop nihan at that time!” Masri remembered complimenting his wife on her beauty on their special day. “I waited for you to finish making the tapis so I could propose to you. And you wore it at our wedding.”

Masri had approached Mak Unyan, sitting on the iron bed she had inherited from her grandmother. The tapis lay in her lap. He had fingered the edge. The gold thread still sparkled. Unyan’s hand embroidery reflected her diligence and patience — the stitches were tight and neat. Her tenacious nature was also evident in the way she cared for babies in the village. No wonder she had become a famous midwife. In his heart, Masri was grateful for being the one to marry Unyan, who, at that time, was favored by the young unmarried men in his village.

Masri recalled Mak Unyan’s happy smile when he retold the story of the tapis and their wedding at her parents’ house. Only after the clergy declared the marriage contract valid, did Unyan come out of her room. Everyone admired her. His wife’s beauty was accentuated by her beautiful tapis. The tightly woven threads were smooth. She had embroidered the cloth with gold threads herself.

Mak Unyan had blushed when he called her beautiful. The two hands Unyan used to deliver children as the traditional midwife in Way Sindi had flown up to cover her embarrassed face. With age, lines had creased her once-smooth face, but Masri cherished each wrinkled memory.

“Congratulations! Your child is a girl!” After helping a villager deliver her baby, Unyan always reminded the new mother to teach her daughter to weave a tapis. “Dang lupa, sanak muleimu ditawaiko napis!”

For the native Lampung people, weaving a tapis is an obligation. During childhood, in addition to reciting the Quran, girls are taught to weave and embroider the sarong-shaped cloth with gold or silver threads. The patterns vary. The Raja Medal pattern depicts human-shaped ornaments; Laut Linau shows butterflies; Inuh carries a marine theme.

Masri knew that unlike the younger generation, Unyan would not forget the traditional weaving technic passed down from her ancestors throughout hundreds of years. The Inuh pattern she had chosen was influenced by her aquatic-rich environment. She had grown up with the oceanic life, for example, ships, seaweed, and sea animals. Although making the tapis took months to complete, Unyan and other girls in her village remained patient and even seemed to be racing each other to see who could complete theirs first. Later, when their wedding day came, they’d wear their tapis as a bride. Likewise, with death, the same tapis would cover their body as a final tribute and honor.

***

Masri kept looking for Mak Unyan’s tapis. Now he moved his search to the dresser in Bayan’s room. Bayan was their only son and still unmarried. Mekhanai tuha, the old bachelor. He had not been interested in any of the muleis in his village. He said he could not find a girl who was as good as his mother at making tapis. It was believed that the results of a woman’s tapis embroidery reflected the nature of the maker. It showed whether she was patient, loving, angry, diligent, lazy — or something else.

Among the girls in the village at that time, Suri was known for being the slowest at weaving. In fact, even the younger weavers left Suri far behind. She had long been secretly in love with Bayan, and even though she was slow at completing her tapis, she kept hoping that Bayan might propose to her as she tried to finish. Bayan, however, ignored her.

Now, watching his father rummage through his dresser for his mother’s tapis, Bayan recalled her asking, “When will you get married, Bayan?”

Bayan understood his old mother’s feelings. She would have loved to guide him to his wedding and pass on her tapis to her daughter-in-law and future grandchildren. “Later, Mak,” Bayan had answered quietly.

“Mak khadu tuha.” His mother’s soft words, reminding him she was growing older, now rang in Bayan’s ears. Not wanting to hurt his mother’s feelings, he had not replied. But his mother continued to encourage him. “Suri is a good girl, go ahead! She is also weaving the Inuh pattern, just like I did.”

“Don’t force me, Mak,” Bayan had retorted as he walked away.

“I’m not forcing you!” his mother called after him. “It’s only a suggestion, just in case you’re a match!” He could still hear his mother’s words.

***

The wind had quickly spread the news of Mak Unyan’s death and the disappearance of her tapis. Neighbors and relatives came not only to mourn, but also to be a firsthand eyewitness that the news was true. They scrambled to be the first to offer their condolences and show their love — while looking for a story to spread.

Most of the mourners would not have believed it if someone had told them what they were going to see: Mak Unyan’s body laid out without a tapis. It was unheard of for a married woman not to have her own tapis. Moreover, Mak Unyan was known as a chatty person who liked to visit the girls making tapis and remind them of the importance of doing so.

Although the wall clock in the living room continued ticking, life seemed to stand still for Bayan. He mourned the loss of his mother and recalled the good days with her. Then, his father’s booming voice snapped him out of his reverie.

“Bayan! Niku pandai di dipa tapis seno?” When Bayan didn’t reply to his father’s direct question if he knew where his mother’s tapis was, Masri rephrased his question, “Ngeliak tapis seno, mawat?”

“Nyak mak pandai.” Bayan’s voice quivered as he spoke his lie that he did not know. He couldn’t believe he was so blatantly deceitful to his father in front of his mother’s dead body. The uproar caused by the missing tapis now made his frantic mind realize how important the cloth was to his family and to the traditional community in his village.

Neighbors continued crowding into Masri’s stilt house. Pairs of sandals lined the first and second steps of the stairs. Even the wind blowing through the wood-shuttered windows could not cool a room filled with so many people.

Masri opened one of the two wide shutters. He took a moment to look out at the rambutan garden beside the house, hiding his red eyes from the mourners’ probing stares. He tried to tame the rumbling in his chest that had been plaguing him since he found out Mak Unyan’s tapis was not in the dresser. The clear sound of a rooster crowing hit Masri’s ears, sounding like a chorus of chuckles.

“Bayan,” whispered a pengtuha, “go try to borrow a relative’s tapis.” The village elder of Way Sindi did not want the mourners, who were supposed to be grieving, to start gossiping instead about Mak Unyan’s missing tapis. “It’s okay. Get your mother a tapis to cover her before the funeral, as a form of respect.”

As Bayan nodded to the pengtuha, Suri arrived with her family. Upon hearing the news of Mak Unyan’s missing tapis, Suri thought about the old woman’s kindness as a close neighbor. Suri asked her family’s permission to leave and hurried back home.

When Suri returned, she held the tapis she had just finished. “Nerima nihan, Suri.” Bayan thanked her and took the tapis from Suri’s hand. Their eyes met. Bayan sensed Suri’s sincerity and saw proof of his mother’s words spoken a long time ago. Suri was truly a good woman.

“Jejama, it’s my pleasure,” Suri replied, softly and warmly. This was the first time she had stood face-to-face with Bayan, and her heart pounded. She wondered why, all this time, the man in front of her had treated her so indifferently. Awkwardly, Suri helped untie the tapis so Bayan could spread it out.

Bayan replaced the long cloth covering Mak Unyan’s body with Suri’s tapis. Suri, the woman his mother had always praised, but he had ignored. Regret crept into his grieving heart. Suri looked sincerely happy that her tapis was being used first at Mak Unyan’s funeral, instead of at Suri’s own wedding day. Secretly, Suri felt touched.

At the end of Mak Unyan’s funeral service, a sad and solemn atmosphere filled the wood house. Verses from the Quran were recited. Occasional sobs mixed with whispers about Suri and Bayan traveled among the mourners.

Masri stopped his search when he saw that another tapis had been placed over his wife’s body. Still, his anger was hard to hide. Fluctuating between sadness and annoyance, he tried to remain patient while shaking hands with mourners offering their condolences.

Bayan sat weakly beside his mother’s body, unable to stand to receive the mourners still arriving. His memory drifted to the Caucasian woman he had met on Pisang Island a week ago.

“Sarrah.” The Caucasian woman’s voice, as she said her name and shook his hand, still rang in Bayan’s ears. Her beauty had transfixed Bayan, and he could not stop thinking about her. The woman, an Australian tourist, had come to Indonesia, especially to the Lampung Province, to conduct research on tapis and write about it. She had talked a lot about the beauty of Indonesian culture — and the tapis cloth, an intangible cultural heritage from Lampung.

“I came here to see the tapis,” Sarrah had stammered excitedly in Indonesian. “I heard that the tapis cloth made in this village is famous for its neat embroidery and beautiful patterns.”

“That’s right!” Bayan had said proudly. He had seen for himself how beautiful the tapis cloths made by the girls in his village were — especially his mother’s. He had felt compelled to prove it.

***

Now, sitting beside his mother’s body, Bayan regretted his rash and thoughtless behavior. Rubbing his face and head, he felt encircled by dancing, golden threads. His mother’s face, tightly covered beside him, appeared in his mind’s eye.

Even though Suri’s tapis now covered his mother’s body, Bayan cursed himself. He imagined his mother patiently making hers but, at the end of her life, the traditional cloth could not even be used for her funeral.

Bayan jumped up from his seat and hurried to the door.

“Bayan! Bayan! Haga dipa?” The mourners asked where he was going. He ignored them and paid no attention to the calls from his father and Suri. Instead, Bayan broke into a run, his heart giving way to his anxiety and fueling his legs as he raced through the bushes toward the beach. He took unused paths so no one could see him.

Three kilometers away, a small cabin stood with windows facing the sea. He had to retrieve Mak Unyan’s tapis before her body was taken for burial.

*****

Batimbang Safar

Atikah Yuniar Rahma was born in East Kalimantan and raised in South Kalimantan. Rahma has been fond of reading all her life. As she grew older, she explored various reading genres, such as poetry, short stories, and novels. Her desire to become a writer began with her interest in reading literary works.

In 2021, she continued her higher education in the English Language Education Study Program, at Mulawarman University. Rahma participated in the English Language Education Student Association at the university. She also interned as a teacher for four months in the Kampus Mengajar Program organized by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology. During her senior year of college, Rahma spent seven months teaching with fellow teachers at the English Legion Language Training Institution. While conducting research for her thesis, she wrote short stories. Batimbang Safar is her first published short story.

Atikah’s winning question: As an academic and an author, what is your most proficient method of writing?

Atikah Rahma at atikahyuniar@gmail.com

***

Batimbang Safar

Gia berdiri di tepi jalan tempat pemberhentian sementara kendaraan. Dia baru saja tiba dari Pulau Jawa tempat kerjanya dan sedang menunggu mobil antar-jemput. Kali ini Gia tidak dijemput oleh ayah atau kakaknya. Ayahnya sakit dan kakaknya sedang sibuk dengan pekerjaannya. Sudah lebih dari setahun Gia tidak pulang kampung ke kota asalnya, Tanjung Tabalong, Kalimantan Selatan. Di kecamatan itu dia dilahirkan dan dibesarkan hingga menempuh bangku Sekolah Menengah Atas. Untuk sampai di sana dia masih harus menempuh perjalanan darat sekitar lima jam lagi dari bandara Syamsudin Noor dengan menggunakan kendaraan umum.

Tabalong adalah sebuah kabupaten di Kalimantan Selatan, sedangkan Tanjung adalah kecamatan yang menjadi pusat kabupaten itu. Namun, orang sudah biasa menyebut kecamatan itu Tanjung Tabalong. Bahasa yang digunakan sehari-harinya adalah bahasa Banjar dan bahasa Indonesia, sama dengan daerah atau kabupaten lain di Kalimantan Selatan. Di kota yang tidak terlalu ramai itu, adat dan budaya serta kearifan setempat masih banyak diterapkan dalam kehidupan bermasyarakat.

Di dalam lubuk hati Gia, ada perasaan rindu dengan kampung halaman. Rindu akan udaranya yang sejuk, makanan khasnya, terutama masakan ibunya, dan rindu bertemu dengan kawan lamanya.

Satu jam lagi Gia akan tiba di rumah. Dia memandangi suasana kecamatan Tanjung Tabalong dari balik kaca jendela mobil. Ada beberapa perubahan yang terlihat menghiasi pusat kabupaten itu. Tampak gerbang nan megah di jalan baru, jalan yang dibangun untuk pengembangan dan perluasan kota. Selain itu, berdirinya bangunan baru berupa ruko di tanah kosong dekat pom bensin sepertinya sudah siap huni. Keadaan jalan juga dirasa lebih mulus dibanding keadaan sekitar setahun lalu, ketika dia terakhir kali pulang untuk menghadiri pernikahan Al, kakaknya.

Mobil membawa Gia tiba di lampu merah tugu obor yang sangat terkenal karena kekhasannya. Bangunan termasyhur itu mengeluarkan kobaran api dari pipa gas yang disalurkan oleh perusahaan gas milik negara. Karya seni dengan kobaran api yang dia lihat saat ini sangatlah bersinar karena dikelilingi oleh lampu-lampu hias berwarna-warni yang terlihat lebih jelas di kala malam. Gia terbuai dalam lamunan.

Mobil yang membawa Gia melanjutkan perjalanan berbelok ke kanan, ke wilayah permukiman Tanjung Bersinar. Rumahnya berada tidak terlalu jauh dari pintu masuk perumahan. Sebelumnya, dia telah mengirimkan sebuah pesan kepada ibunya bahwa sekitar lima menit lagi dia akan tiba di rumah.

“Pak, berhenti di situ ya. Rumah warna abu-abu berpagar hitam,” kata Gia pada sopir. Gia yang duduk di kursi belakang pengemudi sejak tadi pandangannya tidak lepas dari teras rumah yang tampak dari kejauhan. Mobil berhenti tepat di depan rumahnya, dan dia melihat kedua orangtuanya dan Al yang beranjak dari teras dan berlari kecil menuju ke arah gerbang pagar yang terbuka.

Sopir turun dan melangkah ke arah belakang mobil untuk mengeluarkan koper Gia dan beberapa tas berisikan oleh-oleh. Gia membuka pintu mobil, bergegas turun sambil membawa tas punggung, dan langsung menghampiri orangtuanya.

“Mama, Abah!” Gia memanggil kedua orangtuanya dengan senyum lebar menghiasi wajahnya.

Gia meraih uluran tangan Mama dan menciumnya, lalu mencucup tangan Abah, kemudian Gia memeluk keduanya. Tidak lupa, Gia juga mengecup tangan abangnya yang sekarang telah menjadi seorang ayah.

“Sehat, Nak? Gimana perjalanannya?” Mama merangkul pundak Gia dengan tatapan penuh kasih.

“Alhamdulillah baik Ma. Lancar aja,” Gia kembali memeluk Mama.

“Abah sehat, ‘kan? Gimana kakinya yang jatuh minggu lalu? Masih bengkak?” cecar Gia menanyakan kabar Abah.

“Iya Nak, sudah berkurang sakitnya,” Abah meyakinkan Gia sambil mengucapkan hamdalah.

“Kak Laila mana, Bang?” Gia bertanya kepada Al keberadaan kakak iparnya.

“Ada di kamar. Lagi menyusui si kecil. Nanti Abang panggil.” Al mengambil barang bawaan Gia yang bergegas menghampiri sopir untuk membayar ongkos perjalanan. Kemudian Gia, Abah, Mama, dan Al masuk ke dalam rumah.

Gia dan Abah berjalan menuju ruang tamu. Mereka kemudian duduk di kursi. Mama menuju ke dapur sambil berkata, “Mama mau bikin teh sekalian kopi buat Abah.”

“Iya Ma. Jangan terlalu manis ya tehnya!” Gia menaruh tas punggungnya di atas kursi di ruang tamu.

Al menaruh barang bawaan Gia di samping kursi panjang itu. Setelah itu, dia ke kamar untuk memanggil Laila.

Beberapa saat kemudian, Al kembali ke ruang tengah bersama Laila dan si bayi dalam gendongannya.

Gia bangkit dari duduknya dan menghampiri kakak iparnya, mencium tangannya lalu mengalihkan pandangannya ke bayi perempuan dalam gendongan kakak iparnya. “Ihh lucunya keponakanku. Mirip banget mukanya sama Abang. Gemas tante Gia liatnya.” Gia memandang keponakannya sambil memainkan jemari mungilnya yang lembut. “Gimana Kak Laila kabarnya, sehat?”

“Sehat Gia,” senyum Laila merekah.

Ingin sekali rasanya Gia menggendong keponakannya, tetapi dia menyadari belum membersihkan diri. Al dan Laila tersenyum melihat Gia menarik kembali tangannya yang terulur untuk menggendong keponakannya.

“Gia ada bawa oleh-oleh kesukaan Abang,” Gia berkata sambil berjalan mengambil tas oleh-oleh di samping kursi panjang. “Ini ada bolu lapis talas Bogor, khusus untuk Abang.”

“Wih enak nih. Tau aja kesukaanku. Makasih ya.” Al tersenyum lebar menerima pemberian adiknya. Mereka pun bersama Abah duduk di kursi tamu sambil makan oleh-oleh lainnya yang dibawa Gia, yakni bika Bogor talas ubi dan keripik pisang.

“Gimana kerjaanmu? Ga mau coba cari kerja di sini?” Al bertanya di sela menikmati oleh-oleh.

“Belum ada rencana sih, Bang. Mau cari pengalaman dulu lah,” jawab Gia sembari meraih keripik pisang.